- Local Survivor registry

- ALBERT L. STAL

- Local Survivor registry

- ALBERT L. STAL

Survivor Profile

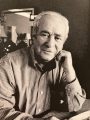

ALBERT

L.

STAL

(1926- 2015)

PRE-WAR NAME:

ALBERT L. STAL

ALBERT L. STAL

PLACE OF BIRTH:

PARIS, FRANCE

PARIS, FRANCE

DATE OF BIRTH:

1926

1926

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

RUE VANDREZANNE, PARIS, FRANCE

RUE VANDREZANNE, PARIS, FRANCE

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

RUE VANDREZANNE, PARIS; VICHY FRANCE

RUE VANDREZANNE, PARIS; VICHY FRANCE

STATUS:

CHILD SURVIVOR

CHILD SURVIVOR

RELATED PERSON(S):

STRUL MENDEL STAL - Father (Deceased),

LIBA NACHA ENGLENDER STAL - Mother (Deceased),

SALOMON STAL-BROTHER (Deceased),

MARGUERITE (MARGOT)-SISTER ,

EVA STAL - Spouse,

JEFF STAL - Son,

LISA STAL BRODKIN - Daughter,

DARRYL STAL - Son

-

EXTENDED BIOGRAPHY ADAPTED BY NANCY GORRELL FROM DIVIDED JOURNEY

Extended Biography adapted from Divided Journey: A Story of Survival of the Holocaust in France During World War II by Albert L. Stal with Israelin Shockness (2012).

It is my hope that my autobiography, an account of the atrocities that I experienced and which deprived me of my family at an early age, would impress our younger people that racial discrimination and intolerance are inhumane practices that have no place in civilized societies.

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

I see this experience as that of a journey, one that began in Poland in the 1920s, with an intense and “dark” stopover in France, and with a final leg of the journey taking place in the 1940s and ending in Canada. Although it has been a difficult and divided journey, it has been one that was inspired by fear and doubt, initiated by hop, bolstered and nourished along the way by great courage and conviction, and despite periods of near despair, concluded with great happiness. Yet it is a happiness that would forever be spotted with sadness. This divided journey is one that I have shared with my parents and my siblings in my early years, and with millions of Jews around the world and across different generations in later years.

Albert writes that his inspiration for his autobiography “surfaced as I heard personal testimonies of Holocaust survivors during Holocaust education week in Toronto. I realized then the responsibility of survivors to add to the store of knowledge about the Holocaust.” His years had “not deprived him of some of the gripping sensations” that left an “indelible mark” on his life, considering he had “replayed many atrocities” he had witnessed in his life “several thousand times in my mind.”

CHAPTER 2

A Family Story Begins

Albert Stahl’s father, Strul Mendel Stal, was born on June 17, 1904 in Poland and immigrated to France at the age of 20. His mother, Liba Nacha Englender was also born in Poland in 1903 and found her way to France in 1920 at the same time that her three brothers immigrated to Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Albert knows little about his parent’s family relations and experiences in Poland in those years save what history records: “Life in Poland during the childhood of my parents must have been difficult considering during the 1905 Revolution, there was a new wave of anti-Semitism sweeping the country. By the time my parents were teenagers, and especially between 1918-1919” . . .there were claims of progroms against Jew most publicized of these was the major progrom in Lvov, the third largest Jewish community in Poland.

Due to the hardships and anti-Semitism in Poland, Albert surmises that his parents decided to immigrate the time was right to immigrate. They chose Paris, France. France at the time needed to increase its population due to the past war. Albert states, “Besides, from all accounts, it appears during this period French sentiment was one of acceptance of Jews.” It was with the “hope for a good life before them, that my mother and father, Strul and Liba, must have decided to make a fresh start in their adopted country: France.”

CHAPTER 3

My Father: Determined and Committed

Albert’s parents rented an apartment and set up their home at 33 Rue Vandrezanne on the 2nd floor of a five- storey apartment building in the 13e Arrondissement of Paris, on the left bank of the Seine River. This apartment was to become the family home throughout the war years. Life was difficult, funds were low, but having left their family in Poland, Strul and Liba “started without delay” creating a new family in France. Albert states, “Though young, my father was a hard-working man who believed in applying himself to all that he undertook. He was a fast learner. Determined to start a family, and committed to progress, his first commitment was to find a job. After arriving in Paris in 1924, he landed his first job in May 1925 with Charles Goldfarb, as a boiseur-tapissier. Later his records show he found work in Sept. 1926 with J. Kliss

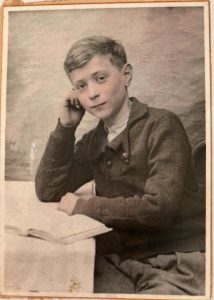

Albert states, “It was just as well he was ambitious, as he was also in process of becoming a father.” Albert was born in 1926 in Paris, identified as a Jew, and the son of stateless Jews (apatrides). Albert recalls little of these early days “except that I had a baby brother, whom I loved a great deal, and whom I played with endlessly. My little brother, Salomon, was born in 1928. Albert was very close with his little brother – ” a closeness that was to continue into adolescence.”

CHAPTER 4

Life on Rue Vandrezanne

As far back as Albert could remember, his family always lived on Rue Vandrezanne. “I can almost close my eyes and magically summon up the vision of this place I called home for so many years.” Albert describes it as a “short, narrow, somewhat convoluted street running between Rue Bobillot on the west and Avenue d’Italie on the east. “For me, this was a very happy place, for the streets were lined on both sides with all kinds of shops and public buildings.” Albert describes candy shops, wine cellars, restaurants, bakeries, clothing stories, tailors, and vendor galore. Albert describes further down the street the low paying apartment building where many of his friends lived. He would see his friends hanging out or going to school, or he would meet Jean or Raymond, his very best friends. In sum, Albert describes Rue Vandrezanne as a small and interesting street in a popular district with unpretentious apartment buildings providing very low rents. All the store owners on this street knew our family and we knew them, and most of the children who lived there were also my good friends.”

CHAPTER 5

Kindergarten and Elementary Days

When Albert was about five or six, he entered kindergarten. Boys and girls attended separate schools. Initially, he recalls enjoying singing French songs and listening to stories, but then on the playground he encountered the violence of boy bullies. He experienced daily cuts and bruises and an occasional bloody nose. Although he found pleasure “in my classroom readers,” I realized that the world was a somewhat harsher place.” Albert was “determined not to be bullied,” and he fought his way out of many situations. But he admits, “there was a cost to this. As an average student, I did not endear myself to my teachers, some of whom expressed the sentiment that I could have done much better in my school work…” Alberts “rambunctious” behavior at school soon became common knowledge at home. There he encountered his father: the disciplinarian.CHAPTER 6

Chapter 6

At Home with the Stals, Mid and Later 1930s

“Life at home was idyllic because of my parents and how they made us feel wanted.” Albert’s mother was a sensitive woman who made sure Salomon and Albert were as happy as happy as they possibly could. Although the early 1930s were “becoming even harder financially,” Albert’s mother with her “thrifty ways” made sure that “we were always well fed and clothed.” Albert’s mother with her “quick mind” and “easy smile” made sure that that Albert and his brother learned it was easier to share than to fight. Albert says his mother was an “indefatigable homemaker” that shared her meager resources with others. Family was something that both my parents cherished. The four of them would play small games, some of which were their own creation. “Even so, what was important was that we were together.” Albert describes his father as “quiet and generally pensive. But while he was very kind, he was also very strict, insisting that we display impeccable behavior. At home, Albert also describes his parents “as not known for strict religious adherence,” yet they were “strongly imbued with the essence of Judaism.” Albert says, “Although we did not participate in any synagogue religious events, we tried to adhere to religious practices, with some compromises with our diet. The highest holy days in the Jewish calendar were noticed but not observed in earnest.

CHAPTER 7

Becoming More Mature

Over the years, Albert’s father’s strong reprimands paid off, and Albert learned to control his “headstrong and impulsive behavior.” He graduated from elementary school in about 1940 and pre-registered at Commercial High School which he began attending in 1941. Albert still had encounters of violence on the streets but he could walk away from a fight. By this time, Albert was making friendships that would last a lifetime. He mentions in particular still corresponding to this day with Harry Meryn and his brother, Jacque, and Jean Bauge, and his brother, Raymond, whose father helped him ward off an arrest by local police in France, 1942 – an unforgettable experience. At 14 years of age, Albert says “he had developed a strong sense of right and wrong. As a teenager, I was shy with girls but interested to meet them.” Albert remembers too the empty shops and their owners driven out of business as a result of the restrictions and the economy. The shopping restrictions were eventually imposed on the Jews, namely, the striction of one hour of shopping per day from 11:00am to 12:00 noon. The local library was to become one of Albert’s favorite places. Albert says, “The library was a real paradise for me, until Jews were no longer allowed to go to the library. . .In time I became a prolific reader, with more diverse tastes, and I started to read political writings.”

CHAPTER 8

The Great Depression in France

Since France was for the large part made up of small farmers, Albert says, “bad financial times were postponed in France until around 1932. According to historical documents, as the Great Depression pushed on, France fell hard into unemployment with about half a million people without work. But France was better off than Britain and Germany because France had food provided by the many French people that returned to the land. Although in the 1920s, Jews appeared to be welcomed in France, by the 1930s Albert says, “there was a dramatic increase in anti-Semitism and xenophobia. Efforts were made to fracture the Jewish population between the Jews that had immigrated to France to escape the progroms and Jews who were French citizens. “The immigrant Jews were considered stateless Jews, as were my parents, and there was a prevalent sentiment that these stateless Jews were taking away jobs from French citizens.” Albert points out that “It was the obvious intention of the French government to alienate one part of the Jewish population against the other. This distinction did not hold up, for when Jews were being sent to the concentration camps, no distinction was made between the Jews who were French citizens and the Jews who were stateless.”

CHAPTER 9

Things Have Changed

In 1934 the economic situation in France was becoming worse along with the rising anti-Semitism and xenophobia. Albert’s father decided he was no longer going to work for J. Kliss and so, he left this employment to start his own business. In May 1935, Albert’s father decided to start his own small business as a self-employed artisan. He leased a small workshop at 40 Rue de Paris in the Les Lilas district on a renewable short-term lease. Albert says “My father took great pride in his work, putting in long hours to realize his dream.” Albert quotes the adage: “A man’s hands betrays all his secrets,” and my father’s hands did just that. He says those hands were “rough, calloused and strong. Those were the hands of a hardworking man, who plied his trade diligently, using the many manual skills he had amassed over the years working in France. . .His spartan office became a well-recognizable sight in the district and my father became well-known for his craft. Hiring horse-drawn carts, my father had his finely crafted beds delivered.”

CHAPTER 10

Our Family Grows

In 1937 my sister, Marguerite (Margot) was born. I remember being happy. Many of my friends had sisters. Albert says, “It was a tremendous time of joy for our family. But again, this came at a cost. It meant having more space restrictions. My parent’s master bedroom now accommodated a crib where my baby sister would sleep. A double bed now fitted well into the adjacent bedroom which Salomon and I were to share. Despite the shortage of space, we learned to make due with our apartment.” Albert says, “We never traveled out to other places because the money father made was barely enough to keep us housed and fed…While the apartment was basic and the walls almost bare, a grandfather clock and a portrait of my parents were the decorations that stood out and declared ‘this is home’ modest though it was.’” Lastly, Albert concludes the chapter with the “most significant and serious aspect of their apartment – the entrance. Although we did not attend synagogue, there was never any doubt as to our identity. We were Jews. This was clearly announced to anyone who came to visit. A MEZUZAH with its tightly folded parchment scrolls proudly heralded at the entrance of our apartment that it was a Jewish home.

CHAPTER 11

Some Hard Times

Chapter 11 concerns a letter Albert’s father wrote to to one of his brothers-in-law in Toronto on October 7, 1935. Written in Yiddish, Albert credits his father as “insightful enough to see that the plight of the Jews was even more precarious than before. . .everyone is walking around in a daze.” Albert also says he lamented, “You can’t imagine had bad things have become in Paris…who knows what lies ahead.” Albert also reveals that at this time he was about 9 years of age and had gained some knowledge of his parent’s families. He knew that his father was the second oldest brother of ten children, and that his parents, Mosh Aaron and Ester Stal, had been living in Poland. I also knew that my mother’s parents were still in Poland but that my mother’s three brothers, my uncles, were in Toronto, Canada. Albert says that in the summer of 1936, France was undergoing significant political change. “A new socialist government, headed by a Jewish prime minister, Leon Blum, was in power. “This incited right- wing groups to even greater hatred and promoted social unrest. Politically involved as a socialist, my father would have been aware of the rise of fascism in France. After all, by this time, Italy and Germany were well under the iron fists of the fascist rulers, Mussolini and Hitler.” (Albert provides an English Translation of his father’s letter).

CHAPTER 12

Making More Than Ends Meet

Albert reports that by the end of the 1930s, his family was making “more than the ends meet.” His father’s business was a success. He worked long and hard to build a reputation, and “it was beginning to pay off.” The quality of his work did not slip and his clientele was satisfied. By 1937, “My mother was busy with Margot, who was well on her way to walking and talking. Playing with Margot was a great deal of fun for Salomon and me.” Albert says that he and his brother were going to neighborhood schools and life was “relatively easy for us. By the end of the decade, the bullying had stopped and Albert had become more studious. He frequented the library and played soccer and went to the movies. “This was a period of growth and development for me.”

CHAPTER 13

The Start of an Eventful Day

According to Albert, “Friday, September 1, 1939 started off as an uneventful day.” The brief chapter, from a child’s point of view, records the reactions of his parents and the adults. The neighbors and adults were gathering in the courtyard. His father looked worried. He revealed that Poland was invaded by Germany with the help of the Soviet Union. “I realized later that the gathering outside was not in anticipation of fun activities but to gather information on the fate of the Jewish people in Poland.

CHAPTER 14

The Second World War

Later that evening gathered around the radio, “I learned the full details of the day, Friday September 1, 1939. Hitler had invaded Poland with the German army and march on Warsaw.” Albert says reports were that Germans had destroyed most of the invaded area and killed over 1200 people. “It was these reports that caused much distress among the Jewish people at 33 Rue Vandrezanne and many Jewish people living in France.” Albert says, “It was not until two days later that Britain and France decided to declare war on Germany for its aggression in Poland.

CHAPTER 15

France is Criticized

Albert says, “While there were criticisms against France and other countries for not doing something more tangible about helping to crush the power of Germany, there were other criticisms that France was not ready for a war.” Although Britain and France had declared war, “they had done nothing to help Poland or to stop the continued aggression by Germany…all talk and no action.” Albert points out that Colonel De Gaulle greatly criticized the French army as unprepared and “not properly trained. They needed training and exercise because the men were not in good physical condition.” According to Albert, De Gaulle’s warnings were ignored by the military bureaucracy.

CHAPTER 16

My Family is Evacuated

Albert testifies that “immediately after declaring war against Germany on September 3, 1939, the French government programmed a frantic evacuation of French families to the south.” The reasons for the evacuation was to make room for its troops in strategic areas and to remove citizens, especially women and children from vulnerable areas of attack. “Paris was considered a vulnerable area so my mother, brother, sister and I were moved south and billeted in a small lodging on the third floor of a white building in Beaupreau, a small town located in the Maine et Loire Department in Angiers.” In the meantime, Albert’s father reported for duty in the French army. The lodging was “not a place anyone could live for any length of time—four cots serving as beds, chairs and tables.” On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded France. Albert says, “It was clear the French forces were no match for the Germans, so there was wholesale destruction among the French forces. But the French forces rallied as best as they could. It was also clear that the Maginot Line was flawed. De Gaulle was right after all.”

CHAPTER 17

Retreat of the Army and the Flight of the People

Albert testifies that “following the invasion of France in May 1940 and the march into Paris in June 1940, the greatest blow for France and the French army was the surrender of territory.” There was a massive exodus of people to the south of France for their own safety. But there were also people “trapped” with nowhere to go that did not leave Paris. As Albert expressed it: “Leave to go where?” Most people fled Paris using whatever means they could. Paris was “relatively empty.” Albert testifies: “Over a short sweep of several weeks the country was disintegrating into the worst period of its history. People fled from city to city without leaders. There was confusion and panic. I remember the entire town of Beaupreau was waiting for the German forces.”

CHAPTER 18

We Meet the Merets (Formerly Modzewiecki)

Chapter 18 is devoted to Albert and his family meeting their cousins, the Merets from Paris, among the thousands of refugees traveling south. They had hoped for refuge in a home or barn in Beaupreau mingling with other refugees. They were “particularly happy that they had met us and that they were able to stop their trek southwards to escape the threat that they faced in Paris…Friends of my mother put the Merets up for several days.

CHAPTER 19

The Nazis in Beaupreau

A few days later the first German troops arrived in Beaupreau. “This was a disaster, and a major French defeat that I was watching as a teenager. All was lost, and I felt quite perturbed that our French nation could not defend itself.” Albert sums up what mattered most: “survival. Within a couple of days, great flags with swastikas were flying everywhere. This was the first war I had ever seen…Not only were we being reminded almost continually that our country was no longer under our control, we were humiliated with the vast number of images that portrayed their dominance and our lack of freedom.”

CHAPTER 20

The Nazis

Albert testifies that “at 14 when I heard the term ‘Nazis’ mentioned, I thought of a murderous bully group that was dominating all aspects of our lives. Having blasted their way into our country, the Nazis impressed me as people without conscience, and who put very little value on life, adopting a murderous and simple attitude toward human life. They had brought death and destruction in their wake.” Albert had also heard stories and reports of the “terrible and hideous things they were doing in other countries, and the fact that they were targeting Jews. As a young Jewish boy, I feared for my family’s safety and for my own.”

CHAPTER 21

Coming to Our Aid

In Chapter 21, Albert describes May 13, 1940, when he heard on the radio Winston Churchill’s “heartfelt” speech to the House of Commons “to wage war by sea, land and air . . .victory at all costs.” Albert concludes: Thereafter, there were reports that free French forces together with Britain, Canada, and some commonwealth countries were coming together to form initial Allies against Germany. Several months later, the Allies included the Russian army, two years later the American army joined the group opposing Germany.

CHAPTER 22

New Administration

Albert testifies that on June 22, 1940, eight days after Paris fell to the Germans, France and Germany signed an armistice whereby Germany was to occupy 3/5th of France’s territory, the other 2/5th of the territory was to be administer by the new Vichy government under Henri-Philippe Petain, a WWI veteran. Albert says, “I remember the great fear and humiliation that the French people, including my family, felt at this event. . .I realized all the French people were in grave peril.”

CHAPTER 23

Return to Paris

Albert testifies, “on returning home, my parents, siblings and I immediately found solace in the apartment we left behind for several months. But things had changed dramatically in the city.” Signs told of what was no longer allowed and posters mainly listed the deaths of hostages. Placards of subversive graffiti were everywhere. People were glued to their radios listening for updates on the war and the state of affairs. “It was clear that ‘la belle epoque’ was gone.”

CHAPTER 24

Changed Motto, Changed Attitude

Of the Vichy government, Albert says, “There was a different tone to government attitude. Instead of stressing liberty, equality, and brotherhood, the government seemed to be stressing French nationality. At first this change in attitude was subtle, and it was not questioned. The French resistance belated moved to include Jews…most French people seemed to accept the racial laws with indifference. They may have pretended not to understand the government’s racial policies; but they seemed to welcome the changes. The vast majority of the French population did not react.” Albert testifies that anti-Jewish propaganda and violence intensified. In early 1941, the German authorities decided that coordination of anti-Jewish measures should be implemented throughout both French zones to solve the “Jewish problem.”

CHAPTER 25

Vichy’s Restrictions on the Jews

Albert testifies that one of the most noticeable restrictions for him at age 14 was that he “could no longer go to the library. Jews were also banned from owning radios, going to the cinema, using public swimming pools, and entering parks. They could not use or travel on the metro, they had to use the last wagon.” Under the Vichy administration, the Paris Prefecture was created to deal with all arrests and police matters as well as to see to it that Jewish businesses were confiscated and passed into German (Aryan) hands. Jews were also excluded from positions of ownership in press, theater and film. In addition, Albert testifies to the anti-Jewish measures of Petain’s Vichy government during this period this critical period of time – “A new law allowed the government to engage in the internment of foreign Jews in special camps. In the occupied zone, the German forces didn’t remain idle, either. French administration was indispensable to the elimination of Jews. The process never varied: registration, despoliation, segregation, deportation, concentration in response to German pressure. Vichy extended its policy to affirm its sovereignty. In October1940, French Jews became second class citizens and together with foreign Jews were rejected in many activities of French society. In April 1941 Jews were forbidden to fill any position that would put them in contact with the public and they were not allowed to travel throughout the country. All Jews were required to register, and strict curfews were imposed.

CHAPTER 26

Registration of the Jews and the Yellow Star

Albert testifies that “in the early months of occupation, all Jews were required to register with their local police stations. These stations were later to become direct centers for concentration camps and eventually deportations. By the end of October 1940, most of the Jews had been registered.” Albert emphasizes, “When Jews were asked to register, this applied to all Jews. When Jews were being sent to labor camps, it didn’t matter whether they were foreign or French Jews. Jews were simply rounded up and sent off to camps. In the occupied zone and with the consent of the Vichy government, “The Wearing of the Yellow Star” was introduced, effective June, 1942. All Jews over the age of six were “forced to wear on the left side of their outer garment, a yellow star as large as the palm of a hand, on which the word “JUIF” in black letters was inscribed. “The wearing of the star made me feel singled out, marked, as something other than French. I was not ashamed of being Jewish, but ashamed that as a French boy I was subjected to this discrimination…My initial reaction was one of dissent, but I was fearful of the many risks I would ordinarily take, if I did not follow instructions. I did not wish to do battle with the new measures. It was no longer much fun travelling the streets of Paris, because it often meant coming into conflict with the authorities in a hostile environment. I had to become a quiet teenager…In fact what I had done at this time was to shut myself off from communicating outside the district because I knew there were no sympathizers with a star wearer.”

CHAPTER 27

Food Rationing Introduced

Albert testifies that food rationing began sometime in the late 1940s. Albert remembers his parents discussing the fact that the French population had to feed the very “soldiers that were invading our land and opposing us.” Those people who lived in the cities had to depend on farmers and there was also a “massive shortage of people to work the farms.” Albert testifies, “The government tried to isolate Jews further by insisting that their identity cards and their food and clothing ration cards had to have the word “JUIF” printed on them to indicate the bearers were Jews. There was always the fear that “this meant that Jews would be given even fewer rations. But an alternate reason may have been based on the fact that these were restrictions as to the times Jews could shop…Milk, bread, sugar, chocolate, butter and all vegetables were becoming a rarity.”

CHAPTER 28

Propaganda Against the Jews

Albert testifies in Chapter 28 how the propaganda machinery in the Vichy government set about to promote French people, but also used a variety of measures to turn the French people against the Jews. . .French citizens would take out big signs saying ‘Jews unwelcome.’ The message that was being communicated in so many ways was that Jews were criminals and were unwelcome in French society.” Albert says the “indifference of occupied populations allowed the murder of millions of innocent Jews and no protest was even heard. The war, prisoners of war, worries and deprivations dominated French opinion. Most French people seemed to have little care about the fate of the Jews.” Albert reports that “knowledge of shootings and atrocities in occupied France were widespread but details about the systematic gassing program in the camps were unknown at the time…The anguish of the stateless and foreign-born Jews and their French children represented the majority of victims of the ‘Final Solution’ to the ‘Jewish Question’ in France.”

CHAPTER 29

Back at School

During the 1941 summer break, Albert preregistered at a Commercial High School at 103 Avenue de Choisy in Paris. The principal was a former captain in the French Army. One day “during a moment of playful behavior, I received an imprint of his right hand on my left cheek for a disturbance caused in the classroom when the English teacher was away. The principal had slapped me so hard across my face with his open hand that his imprint on my face lasted for several days. The slap galvanized the students who saw it. They could not understand the principal in taking such extreme brutal action.” Albert, in retrospect, cannot decide “whether the punishment was intended as a deterrent or “the direct result of an anti-Semitic attitude towards me, a Jew.” Nevertheless, Albert managed to complete two years of education at the Commercial High School, “squeezing out average grades in the first year,” and higher grades the next. Albert graduated but did not continue his education after Thursday, July 16, 1942. “My life that had been so defining was suddenly brought to a halt.”

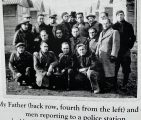

CHAPTER 30

Visit to Beaue-La-Rolande

“On May 14, 1941 Jewish men of foreign ancestry were ordered to report to the nearest police stations…I found out later that they were incarcerated at Beaue-La-Rolande in the department of the “Maine and Loire.” They were told to show up with two days supplies of food and clothing. From later accounts, I gather it is possible that this may have been the first round up of Jews in Paris where more than 3700 foreign Jews were arrested. Albert is unable to recall the specific day, but he testifies to the tearful “family reunion at Beaue-La-Rolande ordered by the French authorities. “Husbands and wives with their children were together in a large field…My mother had brought food and drinks which Salomon, Margot and I consumed with our parents. We knew there was a large internment camp at this location, but as yet, we did not know its full nature. The camp consisted of grey wooden buildings surrounded by high fences overlooked by towers where strongly built guards, armed with guns, kept watch to thwart any escapes. After spending several hours, a siren went off. We embraced, said our goodbyes, as tears welled up in our eyes and poured down our faces…This was the day I will never forget. It was the very last time my father, my mother, Salomon, Margot and I were together. This was also the last time I saw my father.

Albert testifies to the post-war aftermath:

“Following my father’s arrest, we closed his shop which was later expropriated by the French authorities and stripped of all its contents. We never received any compensation for the looting of my father’s business.”

“On August 6, 1946 I was informed by the Ministry that my father had been deported on June 27, 1942 as reported in the list of convoy no. 5. Of the 1038 deportees in this convoy, only 35 survived.”

Editor’s Note:

(Refer to Related Media for Notification from French Government about Arrest, Internment and Deportation to Concentration Camp)

CHAPTER 31

My Identity: Jewish and French

“I knew one thing for sure: I was Jewish and I was French. By age 10 I was well aware of the issues swirling around French society about the Jews…Although my parents had lived in France for twenty years, they were still considered stateless Jews. I remember my parents applying for French citizenship and being denied…My parents had to apply for citizenship for us [all three children] and this was granted]. I considered myself French because I spoke as a French boy.” He also routed for French soccer and cycling teams.

CHAPTER 32

Community Life in France

Albert remembers having many friends, mostly Jewish, but some non-Jewish friends as well. In their apartment building some of the Jewish families came from the same shtetl in Szydlowiec in Poland as my parents. His parents spoke Yiddish with them. In time his parents learned French. “Even when economic conditions were harsh, community life remained a shelter for me, still full of carefree fun before the occupation.”

CHAPTER 33

The Day Before

Albert testifies that Wednesday, July, 1942 “everything was as usual. Our aunt Ita thought it would be fun to take my little sister, Margot, over to her house. Margot and her two young daughters, Paulette and Regine could play together for the afternoon. . .Salomon and I were left at home to amuse ourselves as we usually did.” Albert describes how the afternoon went very fast. “We did not remember until early evening that in a matter of an hour it would be 8:00pm and curfew time for Jews.” They told their mother they could not go and pick up Margot. “The alternative was to allow Margot to sleepover at aunt Ita’s.”

CHAPTER 34

Thursday, July 16, 1942 – An Infamous Day in Human History

Albert testifies it was a summer morning in Paris about 4:00am and still dark. It was July 16, 1942. There was a loud banging at the door, and two French police officers or “agents capteurs” called out, ‘Open the Door” . . . There were no Germans among them participating in the arrests. This was part of the round-up of stateless Jews living in Paris. . .Two police officers ordered my mother to fill up bags of clothing and non-perishable food for the four of us and ordered that the three children be brought out.” Albert’s mother explained that the other two children (Albert and Margot) were away at a relative’s home and not expected to return until later that afternoon. Albert says, “The police officers believed my mother’s explanations and fortunately did not check our apartment where another woman and I were perilously hiding.” Albert’s mother also pleaded with them to accept money and jewelry not to arrest them or to report that the apartment was unoccupied, all to no avail. Albert testifies that “there were two more days of such arrests to go—on July 17-18, 1942, rounding up thousands upon thousands of foreign Jews and taking them to the Velodrome d’Hiver. From there they were transported to two Loiret camps at Pithiviers and Beaune-La-Rolande. . .It was a full four years before I got word about my mother and brother!

On August 6, 1946, I was informed by the Ministry that my mother had been interned on July 21, 1942 at Pithiviers, transferred to Drancy, and from there deported August 2, 1942 to Auschwitz as reported in the list of convoy no.14. Of the 834 deportees in this convoy, only 14 survived.

Editor’s Note:

Refer to Related Media for Notification from the French government about the arrest, internment and deportation of my mother and brother, Salomon, to the concentration Camp

CHAPTERS 35-36

On My Own and Seeking Refuge

Sometime after the police left with Albert’s mother and brother, Salomon, Albert headed for the “underground basement where tenants customarily stored their coal and wood supplies. The ‘cave’ as the underground basement was known, was cold and damp and without electricity.” From time to time, Albert would peak out the door, but no one saw him. When he thought it was safe, he left the cellar to go to get Margot in the Modzewiecky family apartment. “Whether by chance or the providence of God, their presence was surprisingly miraculous. Margot’s eyes lit up when I appeared at the door.” Albert told them about his mother and to hustle and leave their apartment and find refuge with non-Jewish friends. Albert and Margot headed back to their apartment “to face unforeseen and unimaginable decisions seeking refuge.” To his horror, Albert learned that aunt Ita and her husband Wolf Modzewiecki did not heed his warning to leave their apartment and seek refuge. They and their two daughters were forcibly removed from their apartment and arrested by the French police the next day. At first Margot and I were cared for by our cousins, Jack and Rose Modzewiecki, French citizens and residents of our apartment building. Margot and I stayed in our apartment, after all, our apartment had already been raided. “Circumstances were such that I decided we would stay together.”

CHAPTERS 37-38

Spring Wind and No One Could Have Imagined

Later Albert discovers that there was a manhunt code named “Vent Prisonier” or “Spring Wind” which was intended to seize stateless Jews and to take them to municipal buses heading to Pithiviers and other camps. “This was a sad period in history that I will never forget. . .I discovered later that on this day- July 16, 1942 – over 13,000 men, women and children were taken by force from their homes. From what I heard afterwards, the temperatures in the Velodrome d’Hiver never fell below 40 degrees Celsius. They had no food, water, toilets or bedding. “No one could have imagined the monstrous genocide that was underway. . .We were unaware of what lay beyond the French camps and the Drancy transit camp. We did not hear of Auschwitz or other death camps. . .The continent was to become an anti-Semitic hell hole with hate-extremists the cause for future despair.”

CHAPTER 39

Left an Orphan

“As a young teenager, I was left an orphan because of the atrocities committed against the Jews. I was traumatized because of this experience. Both my parents and my younger brother, Salomon were lost to me forever. At 16 I became the guardian of my little sister, Margot, who was only five at the time. As I look back, I see this experience as having deprived me of the love of family, something that I had learned to hold dear all my life.” Albert testifies to the “sense of guilt as to how it was that I was saved and my younger brother Salomon was gone.” Margot and Albert stayed with their cousins Jack and Rose for two weeks and slept fitfully in their fifth-floor apartment. Following this, “we moved to the second-floor apartment when it was safe to do so.” Albert says, “during the day, these two elderly relatives took care of Margot and in the evening, she became my responsibility. When I worked in the country or was away all week, Margot stayed with them, and from there went to school.” Albert testifies: “Besides the extreme grief that I experienced, I also felt I had to try to make as good a life as I could for Margot and me, for that is what our parents would have wanted for us.”

CHAPTER 41

Jewish Ingenuity at Work

Chapter 41 is devoted to Albert’s connection to his high school friend, a “recognized as a genius, with extremely good technical skills in electrical applications.” Jean gave Albert updates on what was happening in the war theater and he shared vital information with other Jewish kids on a regular basis. “We were intrigued with the news Jean received without having any radio.” To Albert’s amazement, Jean “fixed the last message from BBC of London to avoid the German from tracking his contraption with their electrical detection system. We had gotten the news!” The news grew stronger (of Allies successes) as time passed.

CHAPTER 41-42

My Impending Visit to the Police and the Day of the Police Interview

Late in 1942, Albert received a postcard from the French police requesting him “to appear with appropriate identification to answer certain questions.” Albert decided to ask Jean’s father what to do. Should he answer or ignore the summons? “After a lengthy discussion, he devised a plan that would decide my fate and that of my sister, Margot.” Albert describes being “numb with fear” as the day arrived. Nevertheless, he walked towards the police station with Mr. Bauge (Jean’s father), the yellow star well in evidence. Albert testifies that Mr. Bauge accompanied him into the police station and “handed the postcard to the clerk. After a brief introduction, she understood that Mr. Bauge would be speaking on my behalf.” Albert relates how Mr. Bauge represented him and Margot and saved their lives: “Mr. Bauge explained that I was a French citizen, presently working, free of all financial debt, and not a public burden. Several more questions were asked. Mr. Bauge answered each one calmly and confidently. He also explained that I maintained an apartment with my sister and was in good standing with the law. There was never hesitation in his voice. . .After several minutes of new conversation, the clerk opened the register of names and with two strokes of a red pencil, drew two lines across the register, striking our names from the register: mine and Margot’s. The interview was finished and the clerk said, ‘You are free to leave.’ What she actually had done was to delete the names of all the ‘Stals’ from the register. . .As I think back, Mr. Bauge was indeed the instrument that the unseen hand of fate had used to save Margot and me…We had really survived one more time.”

CHAPTERS 43-45

My First Job and My First Room and Board and My Second Job

Albert testifies in Chapters 43-44 that his “greatest need was to find a job to support myself and Margot. I was willing to try any job and found one in a woodworking factory in a small suburban town south of Paris. The wages were very low. . .However, working at this company exposed me to extreme risks.” There was a co-worker there who was a “fierce collaborator, one who was intent on undermining anyone who happened to be Jewish and report that person to the management.” Albert’s second risk was his ride to work. He was always fearful of an arrest or police check for failure to wear the star.” Albert expressed his fears to his cousin Rose of using the daily transport. She arranged with a neighbor near the wood factory where Albert worked to provide him with room and board so he would not have to travel to work. Albert stayed with Madame Cassels until one day she said, “I have bad news.” He had to leave because neighbors are talking “I’m harboring a Jewish boy.”

In Chapter 45, Albert secures a second job at ETS. Branbourget, a local cabinet manufacturing company that “would be a good fit,” eliminating the “risk for me of having to travel long distances on buses and having to face possible harassment from the French police.” One of the foremen and his son like Albert. Albert says he “maintained excellent relationships with my co-workers.” He worked on an assembly line, conditions were harsh, but Albert did not complain. Eventually Albert would move to a different position in the company. Recorded documents confirm he worked at Branbourget from 1942-1947.

CHAPTER 46-47

The General Manager Summons and Unwanted Revelation

Albert testifies in Chapter 46 that he was summoned by the foreman to see the general manager who explained to him that the current payroll and inventory control employee was leaving the office and asked him “Are you interested?” Albert was eager to “put what I had learned in Commercial High School to good use and leave factory work behind…I accepted the offer without hesitation.” There would be a two-week training period, and then Albert would be on his own. He had to punch a clock and wages were hourly. Albert would manage payroll and inventory records from the factory and safe keeping of the store room. In 1943, Albert got an urgent request from the general manager to arrange for the delivery of military furniture to a distant buyer. In the unloading frenzy, “my scarf that was always fastened to hide the Jewish star sewn to my winter coat was exposed for all to see. I quickly pulled the scarf back to its original position.” Albert returned to the office with the two workers “who never revealed my Jewishness…They never gave me away. These two workers earned my respect and never gave me away. It was their silence that helped me survive.”

CHAPTERS 48-56

In Chapters 48-56 Albert testifies to the hardships of working as a teenage boy during the occupation in Paris and the Vichy French government years. He describes the rationing of food, the Nazi’s crushing dissent, the rising resistance movements, and the resistance in the underground. “As I considered the underground resistance movement, I considered it was responsible for saving many children.” In Chapter 54 Albert confirms “Keeping Hope Alive” as he listened to radio reports in early 1943 that the Allies had entered the war theater and were trying to land in France…We hoped that the Allied forces would liberate France. But when?” In chapter 57, “Free at Last?” Albert testifies that on June 6, 1944 a half a million Allied forces hurled themselves at Hitler’s Atlantic Wall…On that day, Jews in France were watching the allied onslaught on the beaches of Normandy from a short distance, with anticipation and great hope. It was a race against time for many Jews who were in the camps to be deported, who were in the process of being deported, and who were still being arrested.” Albert concludes: “Freedom had definitely returned!”

CHAPTER 58

A New French Government

Albert testifies that with the “unconditional surrender of the Nazi forces, France was in disarray as many of the Vichy leaders were thrown out of their positions. DeGaulle set up the provisional government of the French Republic in June 1944 and Paris was liberated in August 1944. In October 1944 the Allies recognized DeGaulle’s government as the legitimate government of France, Petain was to be put to death for treason and several other Vichy leaders were sentenced…people sang in the streets.” Albert testifies: “As late as July 2012, the French President, Francois Hollande, attended a commemoration of the Holocaust, and acknowledged France’s complicity in this ignoble event.”

POST-WAR BIOGRAPHY CHAPTERS 60-END

In Chapter 61 Albert recounts a “Veritable Surprise” visit from unknown relations, Mr. and Mrs. Olivella from Toronto, Canada. Mr. Olivella served in WWI and immigrated to Canada after the war. Albert says, “I knew my mother’s brothers had migrated when my mother had chosen to come to France, but I had not heard about Toronto before.” Mrs. Olivella told Albert that “my uncle had expressed his eternal gratitude, if and when she arrived in France, she would go to the address and find out what she could about his sister and her family. Uncle Victor explained he had lost contact with the family during the occupation.” Though letters, Albert and Margot found out that the Olivellas were “exceptional, remarkable, and caring people.” In Chapter 63, Albert describes “To Canada and Freedom at Last.” After endless meetings with the officials at the Canadian embassy in Paris, “Margot and I were both granted visas. Albert describes leaving the apartment he had known all his life as somewhat difficult. “Although were glad to leave Paris, this apartment was the only place we had lived.” Albert says, “With a mixture of nostalgic sadness and new hopefulness, Margot then 10, and I, then 21, walked out of the apartment and en route to a new life in Canada. “Our uncles, Sam, Victor and Charles, paid for all the fares we needed to reach Toronto and they had sent us the documents which assured us of rites of passage to Southampton, early in the morning in December, 1947. Chapter 66 “Life in Canada Begins” describes Albert and Margot’s reuniting with family. They arrived at the home of Uncle Sam and Aunt Tillie Englender where they stayed for a few weeks meeting other uncles and aunts. Eventually the relatives decided where Albert and Margot would live in the long term: “After much discussion, it was agreed that Margot would live with Uncle Sam’s family and I would stay with our Uncle Victor, who had recently been divorced and was living alone.” Chapter 67 “My first Job in Canada” describes Albert graduating in December 1955 with a degree in accounting and a partnership with Rumack, Seigel & Co. in January 1956. Although Albert remained a bachelor for a considerable time, he filled his days with civic activities and volunteering in the Jewish community of Toronto. Then, in Chapter 70, “A New Life for Me” begins when he meets Eva on a blind date at 26 Almore Avenue North York. “There was no doubt I was really smitten on first meeting Eva. “Eva and I got married in the presence of both families and numerous friends at the Beth David Synagogue in Toronto on May 25, 1965.” Albert says that from that point on, “Eva has been my soulmate, my best friend, and in the years of our marriage, the source of the deepest happiness of my life.” In Chapter 76 “Family Time,” Albert and Eva “take great pride in the people their three children have become. Jeff Stal is a well-respected doctor, specializing in gastroenterology. . .Lisa (Stal) Brodkin is also a doctor of internal medicine, living and working in New Jersey. . .Darryl Stal, our youngest, is an electrical engineer, whose successful company contracts work for the federal government…We adore our five grandchildren who continue to bring joy to us. Although distance keeps us apart at times, we try to visit them as often as possible.”

POSTSCRIPT ALBERT L. STAL (2012)

When my life ends, it is my hope that my autobiography will survive to keep on telling my painful and tragic story of the Holocaust, but will also point out that despite the horrors that have taken up a good part of my life, I was still able with the power of love, of my wife Eva, and my incredible and loving children, to find some peace and happiness.

-

SURVIVOR INTERvIEW:

REFER TO EXTENDED BIOGRAPHY ABOVE

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

Albert L. Stal with Israelin Shockness, Divided Journey: A Story of Survival of the Holocaust in France During World War II (Life Story Treasures, 2012).