- Local Survivor registry

- HELEN KRAWITZ

- Local Survivor registry

- HELEN KRAWITZ

Survivor Profile

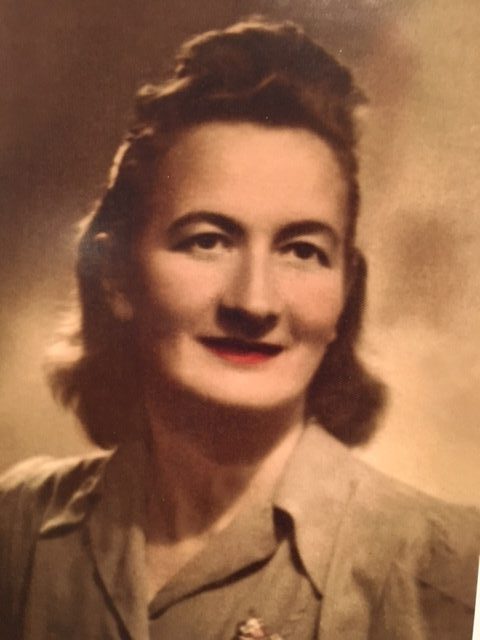

HELEN

KRAWITZ

(1929-2008)

PRE-WAR NAME:

HELENA TURNOWSKY

HELENA TURNOWSKY

PLACE OF BIRTH:

DROHICZYN, POLAND

DROHICZYN, POLAND

DATE OF BIRTH:

SEPTEMBER 29, 1929

SEPTEMBER 29, 1929

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

DROHICZYN, POLAND

DROHICZYN, POLAND

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

GHETTO, DROHICZYN; WARSAW; RUSSIA; SIEMIATZCZE, POLAND

GHETTO, DROHICZYN; WARSAW; RUSSIA; SIEMIATZCZE, POLAND

STATUS:

CHILD SURVIVOR, REFUGEE

CHILD SURVIVOR, REFUGEE

RELATED PERSON(S):

SOL KRAWITZ - Spouse (Deceased),

HAROLD KRAWITZ - Son,

SHARON, JULIE Grandchildren ,

OLIVIA, AARON, TYLER, SIENNA Great-Grandchildren ,

MARK KRAWITZ - Son,

BRIAN, STEVEN Grandchildren - Grandson,

SOLOMON, SAMUEL Great-Grandchildren ,

STUART KRAWITZ - Son,

JOSHUA - Grandson,

SCOTT KRAWITZ - Son,

STEFAN, SASHA Grand-children ,

ISABELLA Great-grandchild ,

EMILIA Great-grandchild ,

HARRISON BEAR Great-grandchild

-

BIOGRAPHY BY SANDRA KRAWITZ AND FAMILY

BIOGRAPHY OF HELEN KRAWITZ

Biography completed by the children of Helen (1929-2008) and Sol Krawitz (1923-2009)

Harold Krawitz, together with his wife, Sandra Krawitz, residents of Somerset County, NJ

Mark Krawitz, together with his wife, Marsha Krawitz, residents of Somerset County, NJ

Stuart Krawitz, together with his wife, Lynda Krawitz, residents of Allentown, PA

Scott Krawitz, together with his wife, Simona Krawitz, residents of New York, NY

Helen was born on September 29, 1929, in the small town of Drohiczyn, Poland, which is located a short distance to the east of Warsaw. She lived here with her mother, Sally, her father, Hyam and her sister, Rose, until the war began. Helen’s mother had two sisters and one brother. Helen’s father was one of seven children. All of Helen’s extended family lived nearby. Her maternal grandfather was an orthodox rabbi who lived his life by the torah.

During her early childhood, Helen and her family enjoyed a comfortable life. Her parents owned a thriving general store, and they were one of the wealthiest families in town.

In the years just preceding the start of the war, however, anti-Semitism became prevalent. Bigoted Poles would picket the store, putting up signs saying such things as “don’t buy from the dirty Jews.”

In 1939, the German bombs began to fall near Drohiczyn. At this time the Germans “gave” a portion of Poland to Russia, and Drohiczyn became a part of Russia. Russian soldiers drove Helen and her family out of their homes, using the excuse that they were “capitalists”, which they claimed was unacceptable in Russian society. They were forced to give up everything and flee to the town of Bialsk, which was about 90 miles away, and near Bialystok, the largest city in northeastern Poland (then “owned” by Russia). Helen was about ten years old at this time and her sister was about seven.

In Bialsk, Helen and her family and all of their extended family found shelter together in a small home, and made a meager living by illegal smuggling. There were no legitimate jobs available to Jews. They were forced to board two Russian soldiers with them. The soldiers occupied the most comfortable room in the house. Of course they had to be extra secretive and careful about their activities with the soldiers watching their every move.

Helen and her family lived this way for more than a year, until the German bombs began to rain down here as well. The family ran from the house, back toward Drohiczyn, and dodged the bombs as they ran, seeking shelter. Sally would cover the bodies of her young daughters with her own body when the bombs were close. They found a hiding place in a cemetery, hoping this was a site that the Germans would not bomb.

The family learned that a friend from the neighboring town of Siemiatycze was willing to take them in. So they made their way to his home, and they lived there for a short while, but anti-Semitism was rampant. The Germans had begun to occupy the town, and atrocities began in earnest.

The Germans instituted an edict, stating that anyone with a beard had to shave it off. This was an obvious affront to the Jews. Helen’s grandfather, the orthodox rabbi, resisted and tried to hide his beard, but he was captured by German soldiers who discovered the beard. They shaved him and set attack dogs on him. The injuries caused by the dogs were so severe that he was unrecognizable when the family was able to rescue him. The experience left him so traumatized that Helen’s beloved grandfather never spoke a word again for the rest of his life.

The family now made their way back to Drohiczyn, where a ghetto for Jews had been created. Having no choice, they took shelter there, where they all lived together in one room. The ghetto was guarded and surrounded by barbed wire so the Jews could not escape.

They lived this way until sometime in 1942, when rumors began to circulate that the ghetto would be liquidated and the Jews would be sent to their death. Sally took the rumors to heart, and she was determined to save her daughters. She took her daughters and ran to the border of the ghetto. With her bare hands she ripped open a section of the barbed wire large enough for her and the girls to escape through. She left her husband behind, assuming she would get back to him once she had found a safe place for their children to hide.

Sally was smart and she was resourceful. Back when she knew the Russians were about to evict her from her home in Drohiczyn and take away her business and all their possessions, she hid some money and jewelry on her person. Now she would put the hidden bounty to good use. From the ghetto, the three of them ran to one neighboring farm where Sally traded money for shelter for one daughter. Then the same procedure was followed on another farm for the other daughter. Each of the daughters was now frightened and alone, hiding on the farm of a non-Jew, who had no real interest in protecting them.

The very next day the Germans did, indeed, arrive at the ghetto to round up the Jews and either murder them on the spot or send them to Treblinka and the gas chambers. About two hundred Jews escaped and ran into the forest. Many were immediately captured and killed. Sally had returned to the ghetto to be with her husband by this time and she and Hyam tried to escape. Helen’s father suffered from asthma and was not able to run as fast as Sally. He fell behind. Sally had to make a difficult choice – should she try to help him or should she continue to run in an effort to save her daughters? Deciding that her daughters were even more vulnerable than her husband, she continued running and made it out of the ghetto. She never saw Hyam or any of the other members of her large extended family again. For a long time she held out hope that her husband had also escaped, but a few years later she learned that someone she knew witnessed his capture by the Germans. There was no longer a reason to hope he had survived.

The local farmers hiding Helen and Rose heard about the liquidation of the ghetto and realized that the German quest to murder all Jews was in full force. They became afraid that the Germans would find the children on their farm and murder them for hiding Jews. The farmers forced the children to hide in the woods during the day, and allowed them to return to the farm to hide under the floor boards at night. The two girls were separate and alone, cold, and almost starving during this period of time. Helen was now about twelve years old and her sister about nine. After several days, Sally was able to make her way back to her frightened daughters.

Now began an even more difficult period for Helen and her mother and sister. They needed to find enough food to survive and shelter from the cold. Many days, if not for frozen potatoes found in the fields, they would have starved. A great deal of time was spent walking in the freezing cold. In the months that followed, many times Helen would think she should have stayed with her father and been murdered in the ghetto, as he was.

Sally would dole out her dwindling supply of money and jewels, but none of the gentile farmers would agree to hide them for long. She would disguise herself as a Polish peasant and go out at night, making her way to the remote farms where the risk of capture was less likely, begging the farmers to shelter them in exchange for money. When she was successful, she would bring back her daughters. At some of the farms the three of them would hide in a small dirt hole covered with straw during the day. At others farms they would hide under the floor boards in the barns until night. They were terribly cramped, unable to fully extend their limbs and with no ability to move or relieve themselves until it was dark. Sally never outwardly despaired, and would not allow her daughters to entertain negative thoughts either. Even though she may have not felt this way in her heart, she told them there was no question about it. They would survive.

Eventually, Sally was able to lead her daughters to the farm of a close friend. He was a non-Jew, and she had entrusted a significant amount of her money to him for safekeeping when the war began. This farmer had a friend in Warsaw, and told Sally that she and her children would be safer there. The friend arranged train passage for them, and although the train was filled with German soldiers, because the girls had blond hair and blue eyes and sat in a compartment with nuns, the soldiers did not ask to see their papers, which of course they did not have.

Once in Warsaw, Sally had to find shelter for herself and the girls separately again, as no one was willing to take all three of them. They had to pass as relatives of the sheltering families, and once again the blond hair and blue eyes helped. Sally would visit the girls once a week to bring more money.

The Warsaw Ghetto had now been formed. As many Jews as the Germans could find had been rounded up and locked into the ghetto. An acquaintance of Sally’s got a message to her that her husband’s brother was in the ghetto and he was very ill and needed help. She needed to figure out a way to gain entry and accomplish her mission, without being trapped inside. A number of inhabitants were brought out of the ghetto during the day to perform work required by the Germans. They would be brought back at the end of the work day, and Sally was able to smuggle herself into the ghetto with one of these groups, and to help her brother-in-law. Of course, she expected to smuggle herself back out and return to her children. Unfortunately, the very next day, while Sally was still there, the Germans arrived. They intended to liquidate the ghetto and send all its residents to the gas chambers.

The Jews in the ghetto knew what the Germans intended, and chaos ensued as the Warsaw Ghetto uprising began. Many of the inhabitants escaped or hid. The Germans set fires and lit dynamite in an effort to kill or burn out the Jews. Within the ghetto, Sally ran from hiding place to hiding place in an effort to avoid the fires. Her hair was singed, but so far she was otherwise unharmed. The Germans continued to set more and more fires. Sally came face to face with a German soldier. She told him “if you let me escape to save my children, your children in Germany will also be saved.” By some miracle, this statement had an effect on the soldier and he let her leave the ghetto. This was April of 1943; Helen was 14 and her sister 11.

Once the uprising began, the girls were forced out of their hiding places. The families hiding them, hearing of the uprising, became fearful that the Germans would search even more aggressively for Jews who were trying to escape. Luckily, the girls were able to find each other. They knew their mother was in serious trouble, because she had not returned to them for an unusually long period of time. They were horrified by the thought that the Germans had finally caught up with Sally and that she had been murdered, leaving them truly alone. They plotted their own suicide, rather than be captured, tortured and murdered themselves by the Germans. Before they could carry out their plan, Sally found them, and they were reunited.

The Warsaw Ghetto uprising was not successful. Most of the Jews who escaped were recaptured and either murdered on the spot or sent to the gas chambers. The Germans were now aggressively searching for the Jews who were still at large, so it became very dangerous to be in Warsaw.

Once again, Helen, Sally and Rose were on the run, back in the woods during the day and walking at night trying to seek food and shelter. Sally heard about a farmer whose livestock and other property had been destroyed by fire. There was no such thing as insurance at that time, so the farmer was in desperate need of money. Sally found the farmer, and once again found shelter for the three of them in exchange for money.

Once more they were hidden in the barn, in a dirt hole covered with straw. They could not emerge from the hole until nighttime. The winters in northern Poland were very cold and they had very little clothing. The farmer dug a hole inside his house so they could stay there during the coldest winter months. If they froze to death his source of income would end. Again there was no opportunity to bathe or use proper facilities. They cut off their hair but became infested with lice anyway. Again, Sally would not tolerate despondency. They would survive.

This particular farmer was not terribly smart, and began bragging to his neighbors that he was buying livestock again and rebuilding his farming business. The neighbors decided that he must be earning money by hiding Jews, and reported him to the Germans. One night, from inside their hole, Sally and her daughters heard a great commotion in the home. German soldiers had barged in; the farmer’s wife and children were screaming in fear. The soldiers threatened to kill the family if they did not reveal the Jews. With guns to their heads, the family denied hiding anyone. The soldiers beat the family and used their bayonets to poke into any potential hiding place they could find. Hearing this from the hole, Helen, Sally and Rose were panic-stricken, but the Germans did not find their hiding place. Once again their lives were spared.

They lived on this farm, in this hole in the ground, for about 11 months. Again it became too dangerous to stay and they had to set out on foot again. They came to a river. Sally still had some money left and she bribed the owner of a small boat to take them across the river to the Russian side, where Sally hoped they would be safer. Here the endless walking and looking for shelter began again. Rose was suffering from tremendous pain in her legs from lying cramped in a hole for such extended periods of time, and one day she sat down and announced that she was giving up. “The Germans can just come and murder me because now I want to die.” Sally pleaded with her to get up, but Rose refused. Finally, Sally told Rose something she never wanted to say. “You think the Germans will just kill you? Let me explain to you what they will do to you before they kill you.” After hearing her mother’s explanation, Rose got up and continued walking.

By this time, they had made their way back to the small town of Siemiatzcze, which was near their hometown of Drohiczyn. They found a friendly person who informed them that many Jews who had managed to escape were hiding in the local forest and had formed partisan resistance groups. These groups were helping other Jews to hide and survive. Sally was introduced to the leader of one of these groups, a young man from Siemiatzce named Sol Krawitz, who would later become her son-in-law. She recognized him as one of the patrons of her general store before the war.

Sol agreed to help them and they were able to stay in hiding with the assistance of this group. The resistance fighters had to be tough. They brought Jews to nearby farms and told the owners that they had to hide them, and if they turned them over to the Nazis to be murdered, the partisans would return the favor and come back and murder members of the farmer’s family. Helen, Sally and Rose were hidden with the help of the partisans until the Russians came and they were told that they could come out of hiding. The Germans had finally been defeated. The three had seen so little daylight for so many years that at first, sunlight was almost painful to their eyes.

Together with Sol, the group was able to return to Drohiczyn where they hoped to find their home and any other surviving family members. Helen’s home had been destroyed and they soon learned the terrible news that no one else had survived in either their family or in Sol’s family. The four of them moved into someone else’s abandoned house with a group of other survivors.

Unfortunately, their struggles were not yet over. The local anti-Semitic Poles had decided to “finish the job for Hitler.” They had stolen the homes and other property of the captured Jews and did not want any of them to return and try to claim what was rightfully theirs. So they armed themselves and formed vigilante groups, attempting to murder as many Jews as they could find. There were no authorities stopping them. Helen and her group now had guns and ammunition and they used their weapons to defend themselves. Many of the other survivors were murdered by the Poles.

To make matters worse, the Russian army had learned of Sol’s activities in the underground, and decided he would make a good soldier for their army. Sol wanted no part of this, and managed to evade the “recruiters.”

Obviously, they needed to leave Poland. They joined a group of other survivors and began walking toward the next country. There were many checkpoints where guards would search the Jews, stealing whatever money or other possessions they could find. They even forced these hapless souls to submit to body cavity searches. Eventually they were smuggled by truck into Czechoslovakia, where they stayed for a short time.

In search of a stable environment and a new life, the group moved from place to place. Like so many of the other refugees, they would steal a ride in the boxcars of freight trains. This practice was hard to police, and transport for survivors was tolerated by many of the train operators. It was dangerous travel, as they had no papers and the men sometimes had to ride on the top of the trains, in the wind and cold.

In Romania, the situation for Jewish refugees was somewhat better. Relief organizations such as The American Red Cross and The Hebrew International Aid Society (“HIAS”) were getting involved and functioning there. So they boarded a train bound for Romania. They were shocked by what they saw on the train. The concentration camps had been liberated and many sick and rail-thin survivors from the camps were traveling with them. They realized that as much as they had suffered, others had suffered even more.

The group continued to travel, in search of better living conditions. Next, they spent some time in Budapest, Hungary, where the Russians were then in control. It was here that Helen became very ill with pneumonia and had to enter a local hospital for treatment. After she was admitted, Sol found out the hospital was terribly overcrowded because of the war, and conditions were so bad that many patients were dying unnecessarily. Sol managed to steal a Russian soldier’s uniform and sneak into the hospital. He smuggled Helen out, and fortunately she recovered on her own.

The next goal of the group became Italy, because they heard that Jews were being smuggled into Israel from Italy. They made their way to Graz, Austria, where they found an English soldier who was Jewish. The soldier agreed to smuggle them into Italy. Once in Italy, they found that tent villages with soup kitchens had been set up for refugees. They lived in a few of these villages as they moved about, trying to find better living quarters. In 1945, they eventually arrived at a displaced persons camp near Naples, Italy, where living conditions were quite tolerable.

Israeli representatives were visiting the refugee villages and displaced persons camps and encouraging Jews living there to come to Israel. That country had its own problems, and was trying to enlarge its defense forces. Young soldiers were urgently needed, and large numbers of refugees, having no better alternative, were emigrating to Israel. Helen, Sally, Rose and Sol really wanted to emigrate to the United States. They heard that their chance for a stable life was better there, but there were so many Polish immigrants waiting entry into the United States, and the quotas were so limited, that they decided to try for Israel instead.

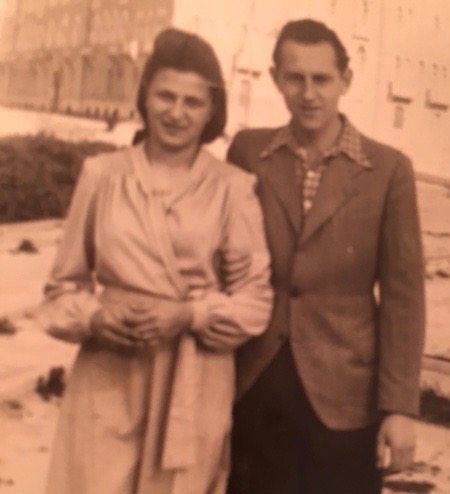

By this time, Helen and Sol had developed a strong loving relationship, but they were informed that since they were not married, there was a risk they would be separated by those in control of transport. After all they had been through together, and since Sol no longer had any family of his own, Sally did not want him to be traveling alone. Helen was 15 years old at this time, and her mother felt that she was too young to be married, but Sally relented. The wedding took place in the displaced persons’ camp in March of 1945.

In later years, when Helen and her sister looked back on what happened in those next few days, they would believe that their mother was blessed with some sort of divine intervention. The group got their vaccinations and prepared to travel. Unlimited immigration into Israel was not yet allowed, so they would be smuggled on board a ship, and hidden during the trip.

On the day of departure, Sally had a sense of impending doom, and said “I changed my mind. We are not going to Israel. We are going back to the displaced persons camp. We will wait and go to the United States when we are allowed.” The rest of the group protested; they were ready to be done with the nomadic life, but Sally was adamant.

So the group went back to the camp, and the ship set sail without them. On the way to Israel, the ship was confiscated and the smuggled Jews were discovered. The ship was forced to dock in Cypress, where all the smuggled Jews had to disembark. They were transferred to yet another barbedwire enclosed ghetto, where conditions were much worse than in the displaced persons camp where they had been living. Again, Sally had saved her daughters from a miserable existence.

Meanwhile, the group waited for their turn to travel from Italy to America. Compared to what they had gone through during the war, life in the camp was peaceful. Sol found ways to earn money by working various jobs. He and Helen would go out on the town and take advantage of the local Italian culture. They went to opera, restaurants, clubs, and so on, determined to have a good time. The newly found freedom was intoxicating, and every night Sol would spend every penny that he had earned that day. After all, who knew what tomorrow might bring?

Finally, Truman expanded the quotas, and they obtained papers for travel to the United States. The night before they were to be transferred to Naples to meet their ship, an unfortunate incident occurred. The men in the camp slept in bunk beds, and Sol was sleeping in one of the top bunks. As a practical joke, the man below him kicked his bed, causing Sol to fall to the stone floor. Sol was seriously hurt and almost died. He suffered a fractured skull and other injuries, and his vision was impaired for life. He was rushed to a nearby hospital where he spent several months being cared for by nuns, who were extremely kind and competent. He was treated by black market drugs, “obtained” by Rose from United States Army troops.

Above Sol’s hospital bed hung a portrait of Jesus on the cross. One day, when Sol was almost fully recovered, a Catholic priest paid Sol a visit. He told Sol that the hospital staff never expected him to recover from his injuries, and having recovered, he should now convert from Judaism to Catholicism. The priest pointed to the picture of Jesus and said “he saved you, so now you belong to him.” Sol remembered his grandfather’s words – “always remember from where you came.” He told the priest he was grateful for the good care he had received from the hospital staff, but that after all he had been through just because he was a Jew, he would remain true to his own faith for the rest of his life; he would not convert.

During Sol’s period of recovery, the rest of the group went back to the displaced persons camp and waited for him to recover. In all, the group spent four years in this camp before they were able to finally travel to America. Through the help of HIAS, a cousin of Sol’s had been located in Milwaukee. The cousin agreed to sponsor them by providing housing and employment for the family. These were the conditions of entry into the US for refugees at that time.

After a difficult and turbulent sailing, the group arrived in New York harbor on a cold day in November, 1949. They had each other, but every other member of both of their families had been murdered. They were penniless, and unable to speak English. The sum total of their possessions was the clothing on their backs.

Sally found a distant cousin, a rabbi, in Borough Park, Brooklyn. This cousin bought them all a bus ticket to Milwaukee. Once they arrived, Sol began work as a butcher, and Helen worked as a housekeeper. In the Midwest, there were very few European refugees, and they felt isolated. They heard that a lot of Holocaust survivors were settling in New York, where they were establishing close-knit communities, and where they were finding opportunities to earn a decent living. The group decided New York might be a better place for them to establish a new life, so they saved enough money to travel to Brooklyn, where they settled. One year to the day after they arrived in New York harbor, their first child, a welfare baby, was born in Brooklyn.

Helen and Sol wanted their newborn to have a traditional bris, but they had no money, and no one other than the four of them to join in the celebration. A rabbi visiting the hospital took pity on them and agreed to perform the bris. “Bring your family in, and we will need a man to hold the baby.” Sol told the rabbi that all of the remaining family was already in front of him; Hitler had taken the rest and there were no men left. The rabbi found a Jewish man in the hospital and told him he was needed to perform a mitzvah. The man resisted, but the rabbi was adamant, so the newborn baby was held by a total stranger, and the bris was performed.

When Helen and Sol brought the baby home from the hospital, Sol began to cry uncontrollably. The experience of that day was an unbearable reminder of the losses they had suffered. In all the years of the war and after all they had been through, Sol never lost control of his emotions as he did on the day of the bris of his first born child. He promised Helen that he would make sure that this child would never feel so alone as Sol did on that day.

Note: Helen’s story continues in the next section about Sol.

BIOGRAPHY OF SURVIVOR SOL KRAWITZ:

Sol was born on December 23, 1923, in Siemiatycze, Poland. His father was mugged and murdered when his mother was pregnant with him. His mother re-married and had 3 more sons, named Meyer, Vafket, and Shula, and a daughter name Gittle. Sol’s stepfather did not accept him, because he was not his natural born child. Sol was made to work hard, and received little comfort in return. He was treated like the “black sheep” of the family. Sol’s mother tried to protect him, but as in many European families, the father was in control. So Sol became a street kid; often he even slept in the street. It was a very depressing childhood.

The maternal side of Sol’s family was large. His grandmother bore twelve daughters and two sons. His grandfather, named Yankel Shushkus, became his one true friend and protector. He would find him in the street and bring him back to his own home. Some nights Sol would sleep in his grandfather’s bed. Sol remembers one of these nights very vividly, when he was about seven years old. In an effort to comfort his grandson, Yankel made a prediction. He told Sol to look very carefully at the painting hanging on the wall in the room, which contained the image of two angels. He said that Sol would face some very difficult times ahead, but that these two angels would always protect him. His grandfather died a few years later, before the war began. Sol was devastated by the loss, and he would remember the story about the two angels for the rest of his life.

Before the war, Sol’s family consisted of about one hundred people. Everyone made a living from the meat business. It was a meager living, however, and money was always short. The family was religious. According to Sol, if you were not a religious person you would be ostracized. Siemiatyzcze had a Jewish population of about six thousand people, and it was a close knit community. Sol described himself as having a strong sense of Jewish identity without being very observant. He did not like to go to synagogue, but he believed in G-d.

When Sol was about sixteen years old, the Germans invaded the neighboring town of Drohiczyn, and began evicting all its Jews from their homes. Among these evicted Jews was a family of four people who had met Sol’s family before and although they did not know each other well, they took shelter with Sol’s family for a short time. One of the children in the family was Helen Turnowsky, who was ten years old at the time. Sol would meet up with her again several years later.

Soon enough, the Germans made their way to Sol’s town and the Siemiatyzcze Jews, including all of Sol’s family, were forced from their homes and locked into ghettos. All of their worldly possessions were confiscated. Not long after, the Germans began to liquidate the ghetto, and load the residents onto trains bound for Treblinka. The Jews knew where they were going. They had already witnessed atrocities at the hands of the Nazis and heard rumors about the gas chambers. As the trains were being loaded, Sol was forced to board a train separate from his family. This was the last time he would see any of his family members.

In later years, Sol would say that maybe it was lucky that he was without family on that train to Treblinka. If he had stayed with the rest of them, his ultimate destination would surely have been the same as theirs – the gas chambers. Maybe it was this feeling of lonely desperation that gave him the courage to do what he did next.

Sol’s train approached a station that was heavily guarded by armed German soldiers. He could see them on the roof of the station. He was a skinny kid, and he and two other boys decided to try to jump out of the small window at the top of their compartment. As the train slowed down, he pushed the other boys out, and then jumped out himself. The train hid them and they scrambled up the side of a berm and out of sight. They were already so close to Treblinka, they could see the fire from the incinerators.

It was a cold November night and the three boys could hear gunshots and screams nearby. They ran in different directions. Sol came to a farm and hid under some hay. At daylight, the farmer came out and discovered him. The farmer told him to “run away or I will kill you, because if the Germans find you here they will kill both of us.” Sol ran and came upon the small town of Bransk. Here he tried to beg for food from the local farmers, but wherever he went he was turned away.

Hungry and cold, Sol lay down near a highway. He could hear the German army passing by. When he felt it might be safe to get up, Sol began walking, and came upon a neighborhood he recognized. He knew some of the residents, and found a Jewish family that was willing to help him. One of their members had already been killed. They told him that there was a group of young men hiding in the woods, and he should try to find the group, as they were helping Jews hide from the Germans. Sol went into the forest and searched until he found the group. Others were joining the group of partisans as well and they began to develop an organized plan for survival. It was now 1941.

The partisans would “visit” the local farms. They were able to obtain some weapons, and then food and shelter for Jews by threatening to perform murderous acts of revenge if the farmers refused to help or turned them in. The Germans were always on the hunt for Jews who might be hiding on the farms.

One day a few soldiers stormed into a farmhouse where Sol and a few others were hiding. Several people were killed. Sol jumped from a window and ran into the woods. The Germans shot at him, but he escaped unharmed. Later he would find holes where the bullets had grazed the sides of his jacket. Sol’s guardian angels were watching over him. Luckily for the partisans, the Germans almost never entered the forest. They knew that armed resistance fighters were hiding under cover of the thick woods and they were afraid for their own safety.

The partisans continued the work of finding hiding places and food. They found a French farmer who agreed to hide some women. He dug a large hole in the floor of his barn in an area where cattle were kept. The farmer kept the hole covered with straw, and hid about fourteen women in this way. Sol and his comrades, walking for miles back and forth, would visit the barn about once a week to make sure the women remained safe.

During this time, Sol’s future mother-in-law, Sally, learned of the existence of the partisan group. For a few years prior, she and her daughters, Helen and Rose, had been running from hiding place to hiding place. Sally searched until she found the partisans in the forest, and Sol agreed to help them by hiding them with the other women in the French farmer’s barn. At this time, Helen was about thirteen years old. She told her mother that she could no longer tolerate being hidden in a hole in the ground. Even though it might be more dangerous, she wanted to stay in the forest with the partisan group instead. Sally and Rose joined the other women and Helen remained with the resistance fighters.

Note: The next part of Sol’s story is contained in Helen’s biography, above, and the story of both Helen and Sol, after the birth of their first child in America, continues below.

Helen and Sol and their newborn son settled into a peaceful life in Brooklyn.

The strength and determination that had allowed Sol to survive the war and its aftermath continued in the United States. Eventually Sol gave up the butcher business and, without any prior experience, moved the family to Allentown, PA, and created a real estate company. Over time, and with relentless effort and hard work, Sol achieved significant success with his business. He and Helen had three more sons and were able to raise their four children in comfort, and to pay for a college education for all of them.

Helen would say that this period of her life was like a fairy tale. It had been many years since she had slept in her clothes, for fear that she would need to run in the night. They had their own home and no one was trying to take it away from them. They had plenty of food and their children were safe and secure. For many years after her children were born, Helen never even wanted to venture outside her home. She just wanted to protect and take care of her family. Of course they had their ups and downs, like any other family, but after what they had been through, life was beautiful. When she was lying in a cold and cramped dirt hole in Poland , Helen could never have imagined what her life would become.

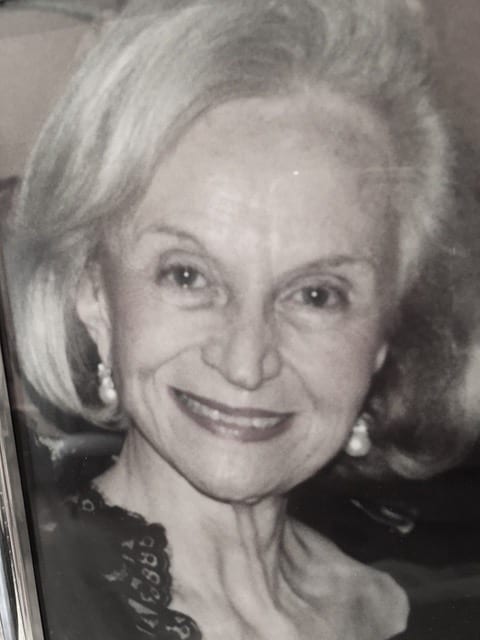

The children grew up, got married, and had children of their own, but they stayed nearby. Helen and Sol were extremely devoted parents and grandparents and they created an intensely close family, which eventually also included 7 grandchildren and 4 great grandchildren.

Helen’s mother Sally died suddenly, of a stroke, at the age of 77. Helen and her sister Rose were devastated that they had not been able to prolong their mother’s life, and save her the way she had saved them.

Helen and Sol were absolutely inseparable for all the years of their marriage. They were totally dependent on each other, as though together they functioned as one person. They never took one day of their lives for granted.

Helen died in November of 2008. Sol was inconsolable and lost the will to live. He died just 10 months later, on Helen’s birthday.

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

Refer to Biography above by Sandra Krawitz and the Krawitz Family

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

Helen and Sol Krawitz Survivor Biography by Sandra Krawitz in collaboration with the Krawitz Family; Steven Spielberg Video Interview with Rose Katzman Grosswirth (Helen’s Sister) 1996; “Sol and Helen’s Testimony,” Krawitz Family Video (Sol’s 80th Birthday) 2002.