- Local Survivor registry

- RENata L.

- Local Survivor registry

- RENata L.

Survivor Profile

RENata

L.

(1938 - PRESENT)

PRE-WAR NAME:

RENATA L.

RENATA L.

PLACE OF BIRTH:

CRACOW, POLAND

CRACOW, POLAND

DATE OF BIRTH:

NOVEMBER 15, 1938

NOVEMBER 15, 1938

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

CRACOW

CRACOW

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

KROSNO, POLAND

KROSNO, POLAND

STATUS:

CHILD SURVIVOR, HIDDEN

CHILD SURVIVOR, HIDDEN

-

BIOGRAPHY BY NANCY GORRELL Of Renata L. (anonymous for privacY)

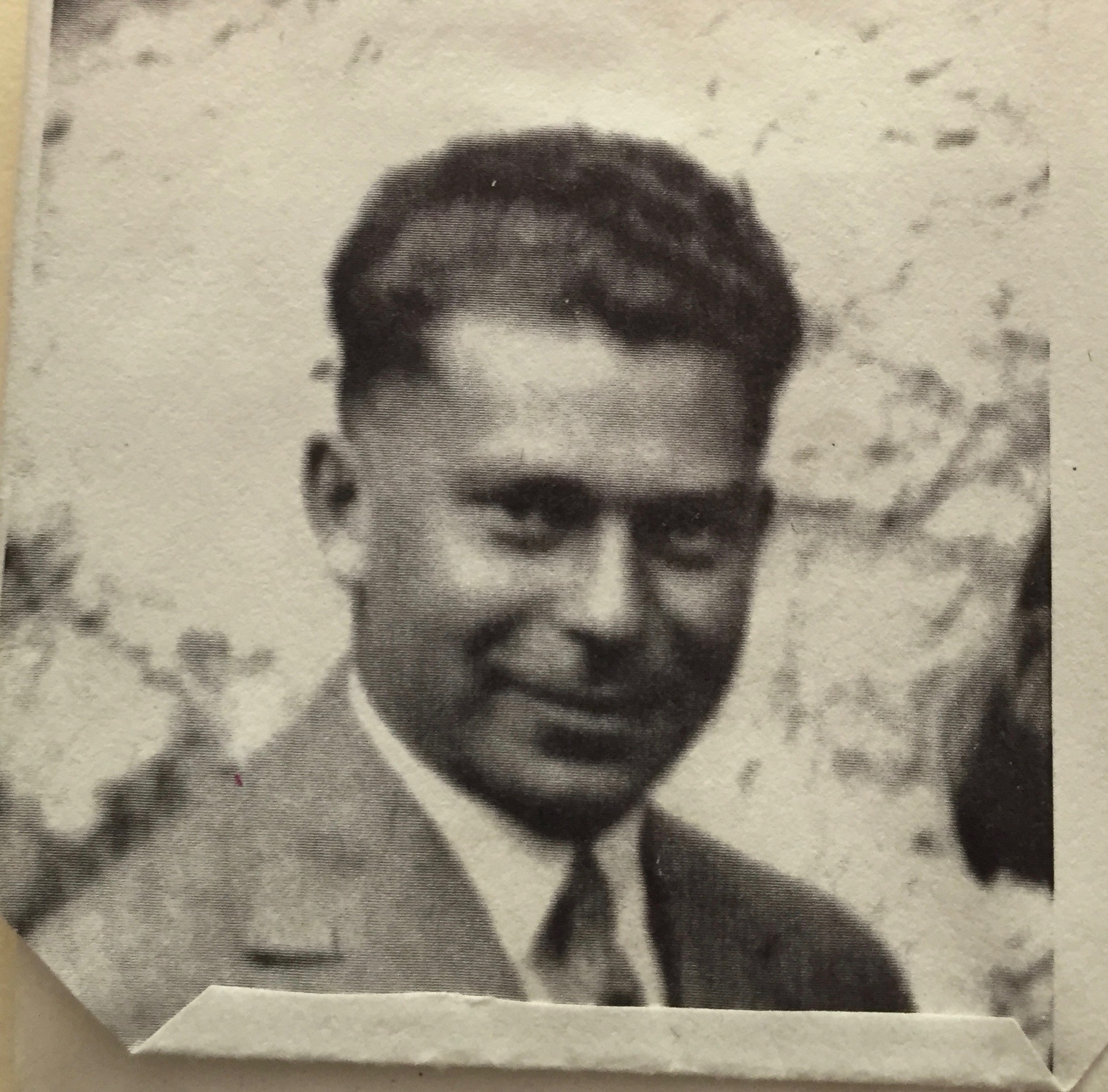

Renata’s parents sent her into hiding when she was two and a half years old. She has only one photograph of her father, Abraham. (Refer to Related Media for photograph). She has never seen what her mother looks like. In her interview, she said:

“I have not a single photo of my mother and have never seen one, and don’t know what she looks like, and this has caused a lifelong heartache.”

Renata was born in the town of Cracow, Poland on November 15, 1938, six days after Kristallnacht. A relative of her father was in Germany at the time and witnessed the destruction. He came back to Poland and tried to warn the family: “Sell everything you own. Put your fortune in a matchbox in the form of diamonds. Put the matchbox in your pocket and leave.” Unfortunately, no one did. Renata came from a wealthy family. Her grandparents owned real estate, a textile factory and oil wells. When Jews began to be rounded up and shot to death, Renata’s parents became desperate to save her life. They brought her to a Catholic family, peasants who used to work for them, and promised them money to hide her. She was two and half years old. She never saw her parents again.

Her peasant family had her baptized. She lost her real name and became Maria Czech, their daughter. Everyone in the village had to believe she was Aryan, or she and her rescuers would be killed by the Gestapo. She went to church with the other children. She recalls in the New York Times column Speaking Personally, “I should have been terrified when I heard them say, ‘Let’s throw her down the well!’” But she did not move or cry out. She was only four or five at the time. Then she heard a women’s voice, “She’s not a dog, after all.”

Between 1940 and 1945, Renata describes her life with the Catholic family as for the most part, “uneventful.” The peasant woman was neither “loving nor bad to me, just indifferent.” When the war ended in May 1945, Renata was six and a half years old. As she recalls, “A man and a woman came to our village.” The man was her father’s younger brother, Sijiek Otto who survived the war in Russia and his wife, Hella. Her uncle was told that, “his brother’s daughter, Renata, who was alive and hidden.” He was also told that she had a scar on her arm for identification. Her uncle and aunt didn’t need the scar. They immediately recognized her because she resembled her father’s face so much. The only picture she has is of her father, Abraham; she’s never seen a picture of her mother.

Renata was told the man and the woman were Jews. She ran away from them screaming, “I’m afraid of Jews.” After their visit, several months passed, but they kept visiting. On one visit Renata recalls running away from the woman and hiding under a bed. “The woman ran after me and she was pregnant, and one of the Polish women threw her down the stairs. The Polish family didn’t want to give me up. I think it was because they wanted the money they were promised for hiding me.”

Her uncle and aunt claimed Renata was their daughter. Then they petitioned a Polish court to legally adopt her. The case went to court and they had to swear they would raise me in the Catholic faith, and eventually, “the authorities let them take me.” It was December 1945, and she was seven years old.

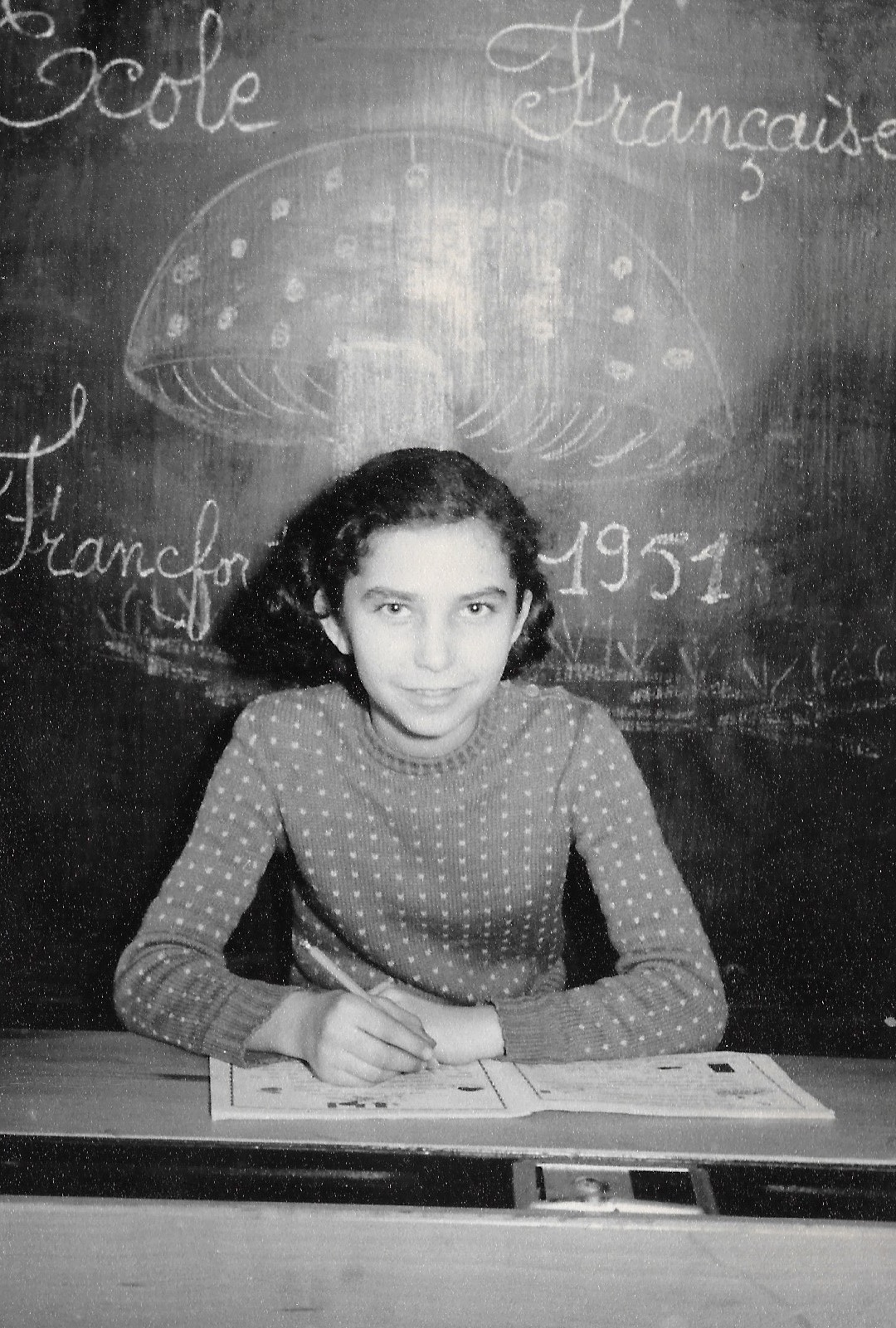

They lived in Katowice, Poland for over a year and then moved to Paris. Renata went to French school and learned the French language quickly but her uncle could not. After two years, they returned to Frankfurt, Germany where he had a business opportunity. From the age of ten, Renata lived in Germany. She went to a French boarding school in Mainz, outside of Frankfurt and eventually received the French baccalaureate degree.

Renata met her future husband at the American Synagogue in Frankfurt when she was 21. They were married in Belgium and came to America in January 1962. In 1997, Renata returned to Krosno and Auschwitz for a return visit.

-

SURVIVOR INTERVIEW:

March 21, 2016

Location: Renata’s Residence

Interviewer: Nancy Gorrell

Q: Describe your background.

I was born on November 15, 1938, six days after Kristallnacht in the Polish city of Cracow. My father’s cousin was in Germany at the time and personally witnessed the destruction. He came back to Poland and tried to warn the family what was going on in Germany. He told them, “Sell everything you own. Put your fortune into your pockets as diamonds and leave.” And they just laughed at him. What did they know?Q: What was your father’s name?

My father was Abraham Isaac . They called him Romek. My mother was Deborah Balkowski . My grandfather came from a wealthy family. They had a textile factory and real estate.Q: What happened to you after Kristallnacht?

I was ten months old when Hitler invaded Germany in September, 1939. When I was two, maybe two and a half years old, I remember my parents giving me to these Polish people who used to work for them. They were peasants and my parents trusted them. My mother said, “Be a good little girl until we come back, and of course, they never came back.” I was with these people until the war ended, May 1945, and I was 6 years old.Q: What was life like living and hiding with these people?

The woman was neither loving nor bad to me. She was indifferent. They were Catholic and they baptized me and gave me the name Maria Czech. I don’t know what their names were. They took me to church, and I don’t know what I knew. I don’t know what I was told. I played with the neighbor kids and sat alone in the street. I remember in church they give you the body of Christ and I got the wafer in church. I remember one time they we fighting with each other, and they were throwing dishes at each other. They had another son who had epilepsy.Q: What did you call her?

I don’t remember exactly, but I’m sure I called her mother because that was the ruse. But I think the villagers kept secret because they knew they’d be taken by the Gestapo too, if they let on who I was. I’m assuming this because every person knew. They took me to church and I don’t know what I knew. I don’t know what I what I was told. I played with the neighbor kids and sat alone in the street. I remember in church and they give you the body of Christ and I got the wafer in church. I remember one time they we fighting with each other and they were throwing dishes at each other. They had another son who had epililesy. I went to Poland 20 years ago and we tried to find the house and the street too. The original name was Ulica Szkolna #8. The village was Krosno. That was the address during the war.Q: What happened to you when the war ended?

When the war ended, a man and woman came to our village. The man was my father’s younger brother, Sijiek Otto who survived the war in Russia and his wife, Hella. He was told Romik’s (my father’s nickname) daughter was alive and hidden. He was also told she has a scar on her arm for identification. They didn’t need the scar. My uncle and aunt immediately recognized me because I resembled my father’s face so much. The only picture I have is of my father; I’ve never have seen a picture of my mother. I was told the man and the woman were Jews. I ran away from them screaming, “I’m afraid of Jews.” Between the time they came, several months passed, but they kept visiting. One visit I ran away from the woman and hid under the bed. She ran after me and she was pregnant, and one of the Polish women threw her down the stairs. The Polish family didn’t want to give me up. I think it was because they wanted the money they were promised for hiding me since my grandfather was rich.Q: What happened to the rest of your family?

My father had been the eldest of six children. His youngest sister, her husband and baby were killed. My father’s parents survived the war hiding in a barn, but on the final days, someone divulged their hiding place. As they tried to escape, they were shot running in a field. To this day, I have never met or heard from a single member of my mother’s family. It’s as if they’ve all been wiped off the face of the earth. Which is exactly what happened.Q: How did you come to live with your aunt and uncle?

They claimed I was their daughter. Then they petitioned a Polish court to legally adopt me. The case went to court and my aunt and uncle had to swear they would raise me in the Catholic faith, and eventually, they let them take me. It was in December 1945. I was 7 years old.Q: Do you remember how you felt?

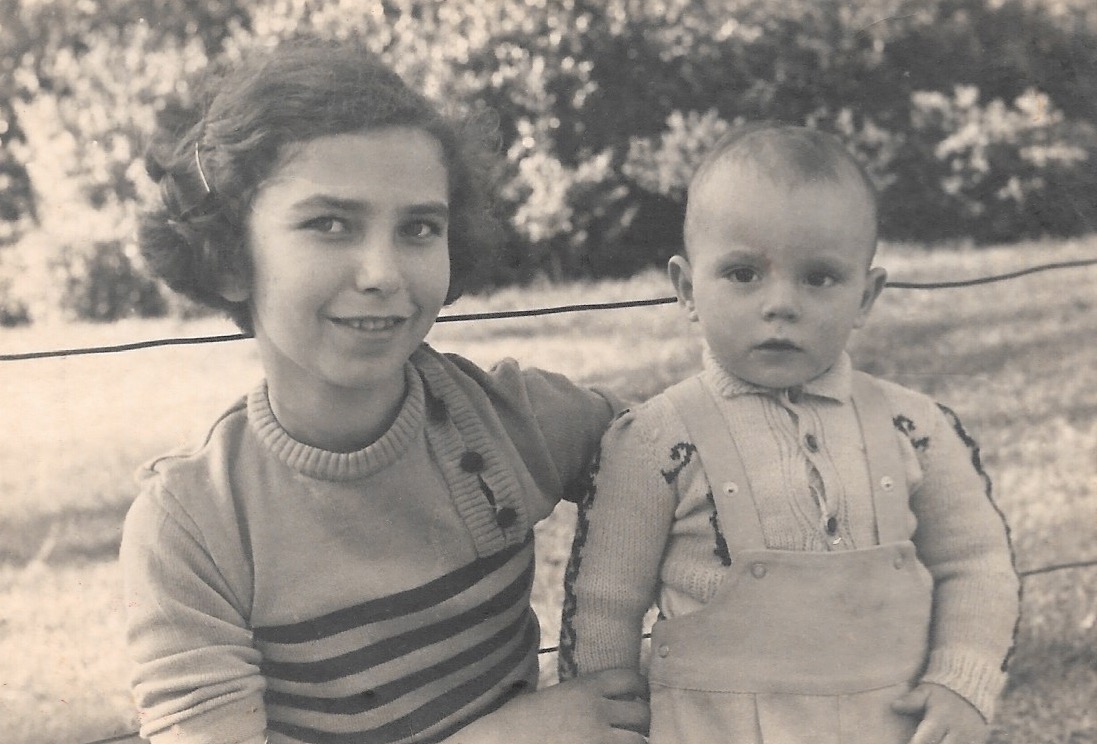

I don’t remember any feelings. I remember the day my aunt and uncle picked me up. We road together in a covered truck and everyone was scared because there was still shooting on the roads. We drove to a town in Poland called Katowice. We lived there for one year after the war. My aunt gave birth to a little boy who lived for two weeks. Katowice is where he is buried.Q: What was post-war life like in Katowice? Did they raise you Catholic?

I went to church with a maid we had. Eventually, I said to my aunt, my adopted mother, “You don’t go to church and your friends don’t got to church, so I won’t go to church.” So I stopped going to church. After one year we moved to Paris. I was 8 years old.Q: What was Paris like?

I lived in Paris between the ages of 8-10 and I went to an elementary French school. One day I was trying to learn French and then after while, I was speaking French fluently. However the problem was my uncle was a businessman, and he couldn’t learn French so easily. So my aunt and uncle decided to go to Germany where he knew the language better. My uncle knew Yiddish and German. And he had some partners there. They were in the textile business. From the age of 10 I lived in Germany. Personally, I think no Jew should have gone back to Germany. I guess it was a matter of economic survival. I never went to a German school. I went to a French boarding school. At the time, Germany was occupied by the Allied armies, and there was a French school for the French occupying army for several years.Q: What city was that in?

Mainz, Germany, less than an hour from Frankfurt where we were living. Every Saturday I took the train to go home on the weekends and then I went back to the boarding school by train on Sunday. At the school I had two best friends: one from Poland and one from Hungary who were also survivors, Felicia and Marielle. I eventually got the French baccalaureate (this degree is two years of college). That was in 1956. After that I went for one year to the University of Heidelberg to be an interpreter. I hated it. Because I don’t always know if it’s the right word!Q: How did you come to leave Germany?

Eventually, my aunt and uncle sent me to America because they realized I wouldn’t find a husband in Germany. So I lived for one year with a cousin in Anaheim, California. I hated the suburbs. So I went back to Frankfurt feeling like a failure and old maid (she smiles). I was either nineteen or twenty years old. Soon thereafter I met my American husband-to-be at the American synagogue in Frankfurt.Q: Tell us more about meeting your future husband.

I almost did not go that Friday night because I was tired. But my girlfriend talked me into it. My school girlfriend Felicia married the chaplain of the synagogue. My parents were 100% against the American soldier, Len, from Asbury Park, New Jersey. He was in the U.S. army in service in Germany. He had stopped college to join the army. So my parents were against it on principle. As an aside, one time we were at the shore at a veterans’ event in America, and my husband asked what does it cost to join, and they asked, “What battles were you in?” and he replied, “The battle of Frankfurt!” It took two years, finally my adoptive parents agreed and then we were married in Belgium, in a town called Knokke, an hour north of Brussels. My adoptive parents were there.Q: When did you go to America?

Right after the wedding. We honeymooned in Bruges and Paris and then returned to Frankfurt and then left for America. The year was December 24, 1961. We lived in South Orange for one year and my husband taught school in Cranford. Then he got a job at Hillside School. We moved to Somerville. By then I had one daughter, age two, named after my mother. My second daughter was the first faculty baby born to a teacher at Hillside school in 1964.Q: What was your career in America?

I took writing courses at the New School in New York City. Since the age of ten I wanted to be a writer. My first story was for the Messenger Gazette, a profile of a teacher named Ms. Gamble. A lot of people knew her. I was a journalist and freelance writer. I went on to write for the Courier, The Daily News, USA Today, 17 Magazine, The New York Times. And I worked full time for 7 years at Woman’s World Magazine as an editor. I also worked for two years before that for a travel trade magazine in NYC. I traveled a lot for the travel magazine to investigate. I’m retired now and we have 5 grandchildren.Q: Did you ever go back to the village where you were hidden?

Yes. In 1997 I took a trip with my husband to Krosno and Auschwitz. All the names of the streets had been changed. We contacted a Polish lawyer through my relative in Sweden who helped us identify the streets and the house where I was hidden. We actually went into the house. There were people there. A lady who looked worried.Q: How did that experience affect you?

I make myself numb. I have no feelings at all.Q: Was the village as you remembered it?

I really didn’t remember much. I was so little.Q: Is there anything else you’d like to add to this interview?

Approximately fifteen years ago, I saw an advertisement for a get-together for hidden children at the Marriott Hotel in Manhattan. It turned out one thousand people attended from all over the world, and they founded a new organization called the Hidden Child which is part of the Anti-Defamation League. The Nazi’s killed one million Jewish children. To end on a happier note, let me say that after we left Poland in 1947 and settled in Paris, my adoptive mother’s second baby was born in November 1948. I was ten years old and thrilled to have a little brother. -

HISTORICAL NOTES:

Historical Note: Kristallnacht

Also known as The Night of the Broken Glass. On this night, November 9, 1938, almost 200 synagogues were destroyed, over 8,000 Jewish shops were sacked and looted, and tens of thousands of Jews were removed to concentration camps. This pogrom received its name because of the great value of glass that was smashed during this anti-Jewish riot. Riots took place throughout Germany and Austria on that night.

-

Sources and Credits:

Credits:

SSBJCC Survivor Registry Interview, March 21, 2017, Nancy Gorrell; Digital historic and family photographs donated by Renata L.