- Local Survivor registry

- ROSE KLUGER

- Local Survivor registry

- ROSE KLUGER

Survivor Profile

ROSE

KLUGER

(1924 - 2020)

PRE-WAR NAME:

ROSE SELINGER

ROSE SELINGER

PLACE OF BIRTH:

TARNOW, POLAND

TARNOW, POLAND

DATE OF BIRTH:

JANUARY 24, 1924

JANUARY 24, 1924

LOCATION(s) BEFORE THE WAR:

TARNOW, POLAND

TARNOW, POLAND

LOCATION(s) DURING THE WAR:

TARNOW GHETTO; PLASZOW LABOR CAMP; AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU II; GUNDELSTORF; FLOSSENBURG; DEATH MARCH; SALSBURG

TARNOW GHETTO; PLASZOW LABOR CAMP; AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU II; GUNDELSTORF; FLOSSENBURG; DEATH MARCH; SALSBURG

STATUS:

SURVIVOR

SURVIVOR

RELATED PERSON(S):

MICHAEL DAVID KLUGER - Spouse (Deceased),

LAWRENCE S. KLUGER - Son,

ADDIE KLUGER - Daughter-in-law,

ALAN JAY KLUGER - Son,

DANIEL J. KLUGER - Grandson,

ALLISON KLUGER STEWART - Granddaughter,

JASON V. KLUGER - Grandson,

NATALIE ROSE STEWART -GREAT - Granddaughter,

MIRIAM SELINGER - Mother (Deceased),

LAZAR SELINGER - Father (Deceased),

JACOB SELINGER-BROTHER (Deceased),

REGINA SELINGER-SISTER (Deceased)

-

BIOGRAPHY adapted by nancy gorrell from Shoah visual History june 29, 1998

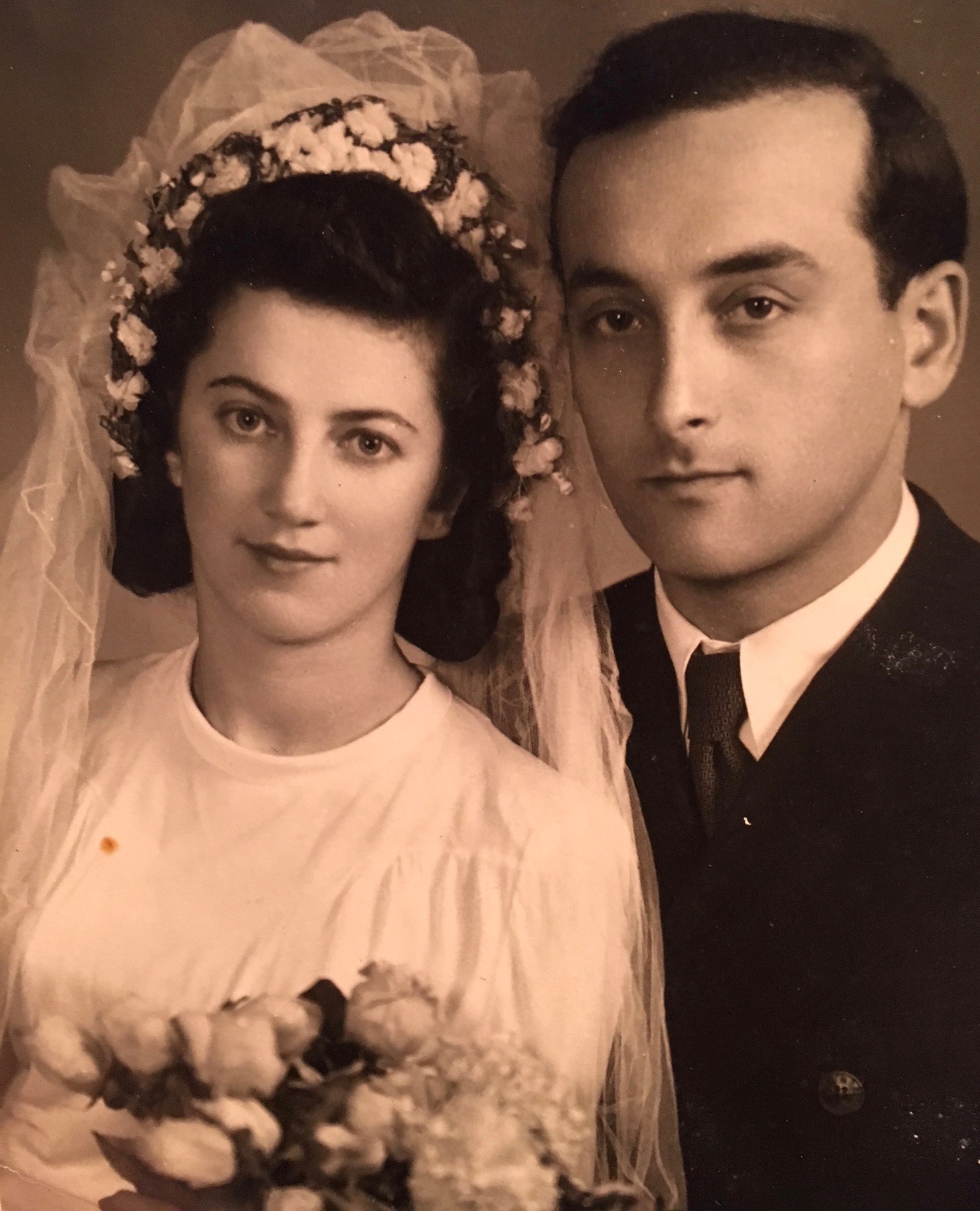

Rose Selinger was born in Tarnow, Poland on January 24, 1924. She grew up in a prominent, loving and tightly-knit family that included her mother, Miriam, her father, Lazar, and her siblings, Jacob (Yakov), her brother, and Regina, her sister. Jacob and Regina were two years apart and 12 and 10 years older than Rose. Rose was babied by her older siblings when she arrived in the home in 1924. Years later, she would say that Regina was almost like a mother to her. They shared a room after she was born. Rose’s father was a prosperous and renowned owner of a shoe factory outside of Tarnow. He was a learned man, loved music, travelled and was often consulted by the town elders on important matters. When asked by the interviewer who she was closer to, her mother or father, Rose answered, “father.” She said she “loved her mother” but “adored” her father. Her father was a “modern” Jew. He did not have a beard, but the family observed shabbat, lit candles and had shabbat dinners every Friday night. The family celebrated holidays. Rose’s favorite was Passover. She says that she never went to synagogue (women did not go). Nevertheless, in Tarnow Rose grew up surrounded by Jews and Jewish life. She testifies that “she had no contact with non-Jews before the war.” When asked if she experienced any anti-Semitism before the war, she replied, “There was no anti-Semitism in Tarnow before the Germans arrived.”

Rose describes Tarnow as a beautiful town with a center 70 kilometers from Krakow. The Selinger family lived in a “nice two-bedroom apartment with a bathroom.” The family spoke Polish in the home. Rose had private lessons in her home learning English and Hebrew before she went to public school. Knowledge of English became critical to Rose post -war and later in America. Rose had no knowledge of the Selinger family going back generations in the region. She never knew her grandparents as they were deceased when she was born (Refer to photo of the grandfather she never knew in Related Media).

Rose had very fond memories of her early childhood in Tarnow. Her family had “Christian” maids that did all the cooking, cleaning and chores. Rose smiled when she admitted she never learned those skill until she married. Growing up her family vacationed in the summers staying in hotels. She loved swimming in the summers and skiing in the winters. She had many friends in Tarnow, all Jewish. She testifies that none of them survived the war. “After the war I couldn’t find them.”

At age six, Rose went to public school. It was across the street from the family apartment. English and math were her favorite subjects. Rose completed grade school and then went on to the public high school. She attended school with both Jews and non-Jews. Her older brother and sister graduated college. Her sister was applying to medical school when the war broke out. Her sister, Regina married a teacher and had a baby boy two years later named Stefan [sic]. Rose says she became an aunt at age eleven. Rose recalls happy memories of her sister’s wedding in Tarnow.

Rose testifies that when the Germans marched into Poland in 1939, “father didn’t run. He tried to buy off the Germans . . . others ran to Russia. . .nobody believed what would happen. . . my father and brother were still working. . .we still had food.” Rose says that they had to move to a different apartment because the Gestapo occupied their apartment for the SS. Rose adds they also had to wear the “armband” and observe the curfew. In 1940 Rose’s father was arrested for the first time and was in prison for two weeks. Rose testifies that “father hid the family money and jewels in his factory in the suburbs of Tarnow.”

1942 was the turning point for Rose and her family. “We went to the ghetto. . .we didn’t see father again.” Only Rose and her brother and sister went to the ghetto in Tarnow. After that, she never saw her father or mother again. In the ghetto, there were two massive deportations of the old, women and children. Everyone in the ghetto worked, endured or were deported. History tells us those deported went directly to Belzec death camp in Poland. (Refer to Historic Notes Below) Rose testifies she worked in the ghetto sewing German uniforms. “Everyone in the ghetto worked. . .We didn’t know anything. We just knew that those deported didn’t come back. . .We did not know of the death camps.” In the last deportation from the ghetto, Rose was separated from her brother and sister. Rose says, “They were only 27 and 25 years old. They could have worked. But my sister had a two-year-old baby.” Rose says, she “never saw them again.” She witnessed unimaginable cruelty in the ghetto during and after the deportations. Rose testifies she saw babies thrown out of windows, and babies, women and children shot during deportations. Rose testifies, “You can’t imagine how cruel human beings can be. After all, the Germans were human.” When the interviewer asked if the Tarnow Ghetto had any resistance, Rose replied, “No. The Tarnow Ghetto was not like the Warsaw Ghetto. They were not shooting people in the streets–only during the deportations.” (Note: History confirms resistance in the Tarnow ghetto. Refer to Historical Notes below).

After Rose was separated from her brother and sister, she was completely alone and lost all will to live. “I didn’t care if I lived or died.” But she had a friend who became a constant companion. That was Helen, five years older than Rose. They travelled together from work camps, concentration camps and death marches. Together they survived. Ultimately, they would be liberated together.

In late 1943, the Nazi’s declare the Tarnow Ghetto “free of Jews.” Rose testifies she was deported to Plaskow, originally a forced labor camp south of Krakow with 80 other girls. By 1944 the camp was enlarged and became a concentration camp. Rose spent six months working there. Rose testifies that Oskar Schindler established an enamel factory in Krakow adjacent to the Plaskow camp. [Note: Schindler moved his Jewish work force to the Sudetenland in 1944, rescuing more than 1,000 Jews].

In August 1944, Rose was transported by cattle car to Auschwitz-Birkenau-II in Poland. There she describes going through a gate and selection–“Left, death and Right, work.” Rose testifies: “We were stripped naked, heads shaved and taken to a room overnight. We were packed body to body. We couldnt move. I could no longer keep my one picture of my mother. In the morning we went to the showers. Our heads were shaved. . . After the showers they threw stripped clothes at us.” Then Rose went to the barracks in Birkenau II. She stayed there for two weeks. There were barracks and toilets outside. “I was tatooed. . .but it’s faded now (Rose shows interviewer her arm). Rose says it was in Auschwitz that she and all the girls stopped menstruating. She says she did nothing for two weeks and then she was transported to Gundelsdorf, a slave labor camp in Germany. She recalls the camp was a three or four hours away by cattle car transport. After Gundelsdorf, Rose testifies she went to Flossenburg. It was winter, snowing, and bitter cold. All she had to wear was her stripped uniform, wet and frozen dress. Rose and the other girls had to work outside from 6:00 am to 5:00pm. They got a piece of bread in the morning and soup at night. “There was a stove in the barrack. We stripped naked and dried our clothes. We survived. The men slept in their wet clothes and died overnight.” Outside they had to work in wooden shoes and their stripped uniform. There were appells (rollcalls) every morning. When asked by the interviewer if there was any religious observance in the camp, Rose answers, “Religion was non-existent in camp. We lost faith.” In late 1944, Rose was transported to an airplane factory in Czechoslavia. She believes it was February 1944 or 1945. Rose and the girls were assembling parts to build airplanes.

Rose testifies the death march began in April 1945. She says SS women led the march. “All we had were our stripped clothes and a blanket. . .people were throwing us bread. . .at night we slept in sheds. . . people were dying like flies. . . .Rose testifies that if you ran away, “They would shoot you.” The death march lasted at least three weeks. “There were 4,000 girls on the march. . .150 left at the end.” Toward the end, she hid with her friend Helen in woodshavings for three days without food, water or shelter. Rose was liberated on May 5, 1945. “I weighed 60 pounds. . .They taught us how to eat in the hospital.” Rose spent two weeks in the hospital recuperating, learning how to eat and drink. Rose says of her hospitalization, “I wondered how you can live and put everything behind you.”

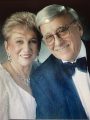

Refer to Michael David Kluger in Local Survivor Registry for Rose’s Post-War and Liberation Story

-

HISTORICAL NOTES:

Before World War II, about 25,000 Jews lived in Tarnow, a city in southern Poland, 45 miles east of Krakow (Cracow). Jews—whose recorded presence in the town went back to the mid-fifteenth century—comprised about half of the town’s total population. A large portion of Jewish business in Tarnow was devoted to garment and hat manufacturing. The Jewish community was ideologically diverse and included both religious Hasidim and secular Zionists.

Immediately following the German occupation of the city on September 8, 1939, the harassment of the Jews began. German units burned down most of the city’s synagogues on September 9 and drafted Jews for forced-labor projects. Tarnow was incorporated into the General Gouvernement (the territory in the interior of occupied Poland). Many Tarnow Jews fled to the east, while a large influx of refugees from elsewhere in Poland continued to increase the town’s Jewish population. In early November, the Germans ordered the establishment of a Jewish council (Judenrat) to transmit orders and regulations to the Jewish community. Among the duties of the Jewish council were enforcement of special taxation on the community and providing workers for forced labor. During 1941, life for the Jews of Tarnow became increasingly precarious. The Germans imposed a large collective fine on the community. Jews were required to hand in their valuables. Roundups for labor became more frequent and killings became more commonplace and arbitrary. Deportations from Tarnow began in June 1942, when about 13,500 Jews were sent to the Belzec killing center. During the deportation operations, German SS and police forces massacred hundreds of Jews in the streets, in the marketplace, in the Jewish cemetery, and in the woods outside the town.

The Ghetto

After the June deportations, the Germans ordered the surviving Jews in Tarnow, along with thousands of Jews from neighboring towns, into a ghetto. The ghetto was surrounded by a high wooden fence. Living conditions in the ghetto were poor, marked by severe food shortages, a lack of sanitary facilities, and a forced-labor regimen in factories and workshops producing goods for the German war industry.

Deportations

In September 1942, the Germans ordered all ghetto residents to report at Targowica Square, where they were subjected to a Selektion (selection) in which those deemed “unessential” were selected out for deportation to the Belzec killing center. About 8,000 people were deported. Thereafter, deportations from Tarnow to killing centers continued sporadically; the Germans deported a group of 2,500 in November 1942. Deportations continued and, in late 1943, Tarnow was declared “free of Jews.” By the end of World War II, the Germans had murdered the majority of Tarnow’s Jews. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/tarnow

Resistance

In the midst of the 1942 deportations, some Jews in Tarnow organized a resistance movement. Many of the resistance leaders were young Zionists involved in the Ha-Shomer Ha-Tsa’ir youth movement. Many of those who left the ghetto to join the partisans fighting in the forests later fell in battle with SS units. Other resisters sought to establish escape routes to Hungary, but with limited success. -

Sources and Credits:

Digital historic and family photographs donated by Lawrence and Addie Kluger.